2025: The Year SwiftUI Died

Rediscovering my love for the Classic UIKit Stack™

2019: Early adoption

SwiftUI released in 2019, to tremendous excitement across the community. Unfortunately, it really sucked for that first year.

I was building a satanic side hustle at the time, and figured I’d go all-in. I blindly cobbled together a global @EnvironmentObject to run the prototype. Push navigation was mostly broken, so I was forced to make every screen transition a modal. I fell in love with the flawed framework.

By the time I did a real startup the next year, I was confident enough to make a proper bet on SwiftUI. This second version, on iOS 14, was much more stable. SwiftUI let me ship faster than I dreamed possible with UIKit. By my third startup, I targeted iOS 15+ and churned out screens like a maniac.

Like all great writers, my story has a 6-year time skip.

2025: The summer everything changed

Two twin technological happenstances collided this summer, transforming the way I work day-to-day:

Firstly, UIKit got some love from Apple. All of a sudden, the iOS 17 @Observable macro was ported to UIKit, alongside updateProperties(), a new view delegate method. It was even back-deployed to work on iOS 18.

Perhaps the eternal MVVM debate between Combine, RxSwift, closures, and binding libraries can finally be put to rest. Or, maybe it will just make the argument worse.

Secondly, agentic AI tools took off in a big way. Improvement in context windows, foundation models, and the tool calling innovation triggered an inflection point where CLI tools started working really well. Pasting code into ChatGPT now feels a bit ‘90s.

Why do people use iOS?

There’s a reason Apple is easy-breezy* when it comes to open-sourcing Swift, xnu, libdispatch, and Foundation. There are myriad security, community goodwill, and cross-platform benefits from keeping these low-level frameworks in the open.

*I’m sure there are several Apple engineers (that aged 20 years during open-sourcing negotiations with legal) who may disagree with the term “easy-breezy”.

When it comes to SwiftUI, UIKit, Core Animation, and most system libraries, however, Apple is ruthlessly guarded.

The difference is clear: Apple is in the hardware business. Integrated system UX is a core competitive advantage, and so Apple does not want you to enjoy their UI frameworks on other people’s platforms.

The secret sauce of iOS has, from day 1, been its characteristic look and feel, what Apple calls the human interface: Interaction. Responsiveness. Animation.

When you drill down into the limits of these 3 pillars, you will find the gap between UIKit and SwiftUI is starkest.

Is SwiftUI ready for production?

For years, developers have asked is SwiftUI production-ready?

For years, the answer has been yes, but.

SwiftUI gets better every year, but is eternally on the long road to parity with UIKit. Even today, basic stuff like camera previews need to come wrapped in a UIHostingController.

SwiftUI also suffers worse performance out-of-the-box due to overhead from diffing view states and dynamic layout computation. This is being worked on, but is fundamentally an architectural choice that may never quite be as fast as UIKit. Every magic system has a cost.

Everybody forgave SwiftUI’s shortcomings because of the undeniable boost to development speed and the tidy ease-of-use the API offers.

But what happens when you’re no longer writing every line of code manually?

Is SwiftUI dead?

This year, UIKit quietly became production-ready again, with Apple granting access to modern @Observable macros and introducing updateProperties().

Simultaneously, agentic AI tooling has trivialised the overhead of writing imperative layout boilerplate. Two key disadvantages of UIKit, slow development and verbose APIs, have been negated. The models are also trained on mountains of UIKit code and docs. Good luck one-shooting fresh SwiftUI APIs like TextEditor.

In 2025, the question is unavoidable:

Should you start migrating back to UIKit?

We need to understand whether SwiftUI can ever fully match UIKit in API capability and performance. Let’s look at the code that reveals the definitive answer.

I won’t tell you how to live your life, but if you want the optimal UX for your users, maximum animation performance, and total control over interactions, UIKit will remain the undisputed king.

Delegates don’t actually suck

I almost cried last year when I touched UIScrollViewDelegate for the first time since 2019.

I was building a cute interaction that animated a line of emojis along a circular path, with their motion along the circle linked to your scroll offset. I could trivially access scrollView.contentOffset.y from the scrollViewDidScroll(_:) delegate method.

Do you know how hard this is with SwiftUI preference keys!?

To be completely fair to SwiftUI, onScrollGeometryChange (iOS 18) can do this now. At the time, I was supporting iOS 17 and couldn’t touch it.

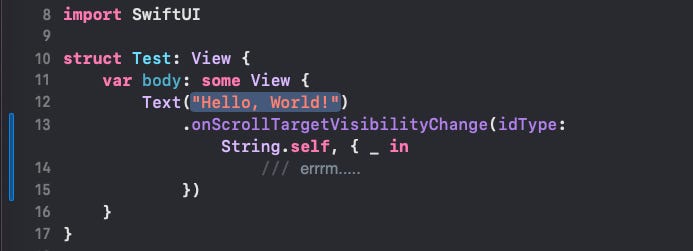

But there are hundreds of UIKit delegate methods that remain unsupported, like scrollViewWillEndDragging(_:withVelocity:targetContentOffset:).

Even if SwiftUI achieves parity with the full UIScrollViewDelegate, we are subjected to a combinatorial explosion of memorisation for new views, view modifiers, and their respective positions on the view hierarchy.

Don’t even get me started on namespacing.

It almost feels like… maybe delegates were actually quite a good pattern for implementing the iceberg of nuance underneath the world’s most complex UI system.

That’s actually a pretty great metaphor…

The UIKit Iceberg

This is the case for pretty much every SwiftUI API that exists. Porting everything from a nearly-20-year-old framework isn’t happening anytime soon.

My controversial opinion about architecture

UIKit lends itself inevitably to “complex” architectures, such as MVC, MVVM, and VIPER. Often, you’ll split your view controller into files for every delegate applied, and every link in the chain of data-flow.

SwiftUI lends itself to simpler architectures, such as the very hot MV approach.

But here’s my edgy opinion:

The more complex your screen-level architecture is, the harder it is to write code. But the easier it is to read. If you keep strict standardisation, you’ll always know where the gesture interactions will live, and what route your data takes as it propagates from tap, to model, to animation.

The simpler your architecture is, the easier it is to write code. With a good design library, you can smash out a SwiftUI screen in an hour. The more you can reduce services into property wrappers, the faster you can ship.

But God help the next engineer who touches it.

The default standardisation from MV is, essentially, “put the stuff wherever”. It just doesn’t lend itself to consistency. Gesture handling will sit on the view that feels the most convenient at the time. If you’re lucky, interaction code sit vertically near to your state, otherwise you’ll just have to search the file(s) to hunt down what touches the data and when.

VIPER is a pain in the arse to write, but frankly, I always knew where to find what I needed.

AI + The Classic UIKit Stack™ = ❤️

This summer, I’ve been making a lot of prototypes, and I’ve been loving the workflow.

I’m rediscovering what makes UIKit so great.

It’s lightweight. It’s performant. I am not hand-coding any constraint boilerplate.

Any interaction I can dream up was built a decade ago. I don’t have to recall or research whether it has been ported yet. It just works.

And a lot of the time, for a complex screen, the code is just easier to read. Which you kind of want when you aren’t typing everything, because effort shifts towards code review of the output.

I wanted to whip up a really simple prototype for you to demonstrate all the ways UIKit is now easier to work with, but accidentally ended up going way overboard and building a full application. It was super fun, I actually can’t stop myself.

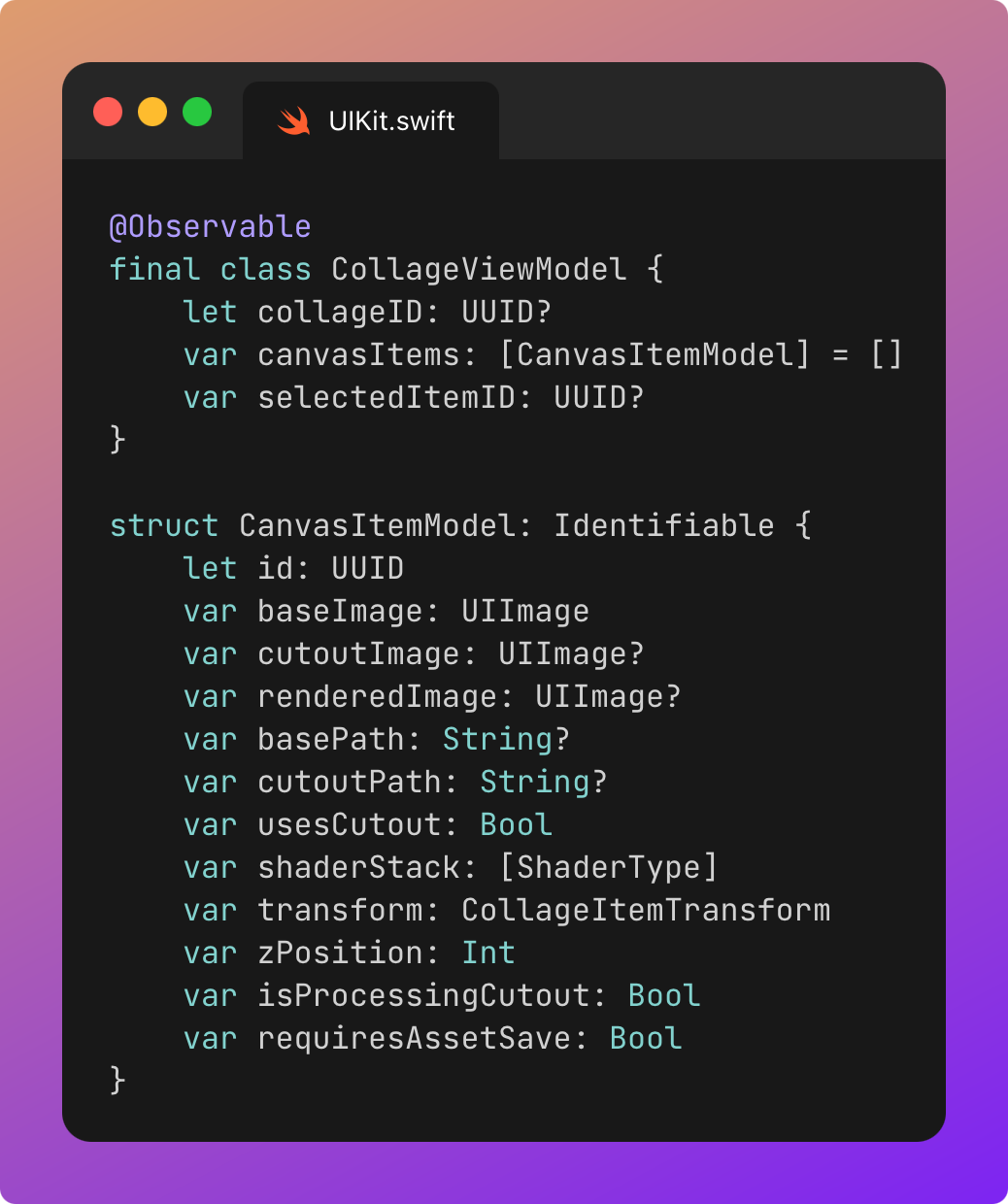

It’s an app that lets you create and edit collages from your photos, apply Metal shaders to them for cool effects, and save them to a gallery.

Every property, transformation, shader ordering, and image file path is stored on SwiftData, meaning that you can save and edit each photo any time you come back to them.

Naturally, I open-sourced it just for this post (prompts n’ all), to demonstrate how nice this workflow is.

I’m going to take you through my process of smashing the app out over a few hours, and give you a gentle reminder of all the beautiful things that UIKit makes really easy for you, as well as demo-ing the new UIKit @Observable pattern.

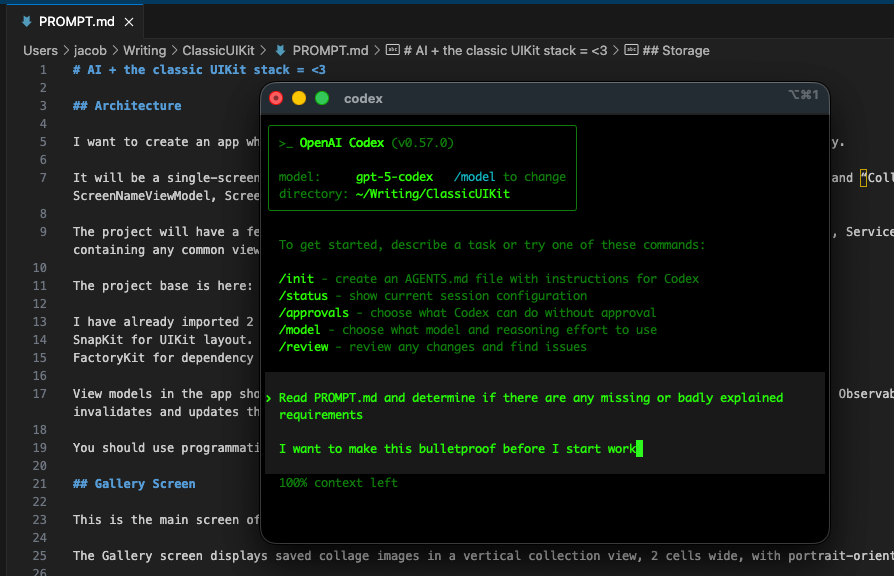

Prompts and one-shotting

Obviously, when you’re working on a live, complex, production app, I’d recommend being way closer to the code, and making smaller changes. But this began almost as a throwaway example app for this article, and I got carried away.

If you actually care about quality, then one-shotting with AI is a myth. But you can get pretty damn close with a clear prompt and a good eye for code review.

The secret is actually not a secret at all. You just need to explicitly detail every requirement. If you’re doing it properly, this might take a good hour. You don’t want to skimp on any details or interactions.

Before you do anything, you need to create the basic project template in Xcode, because the clanker will get the Info.plist and build settings very wrong.

Actually reading your code

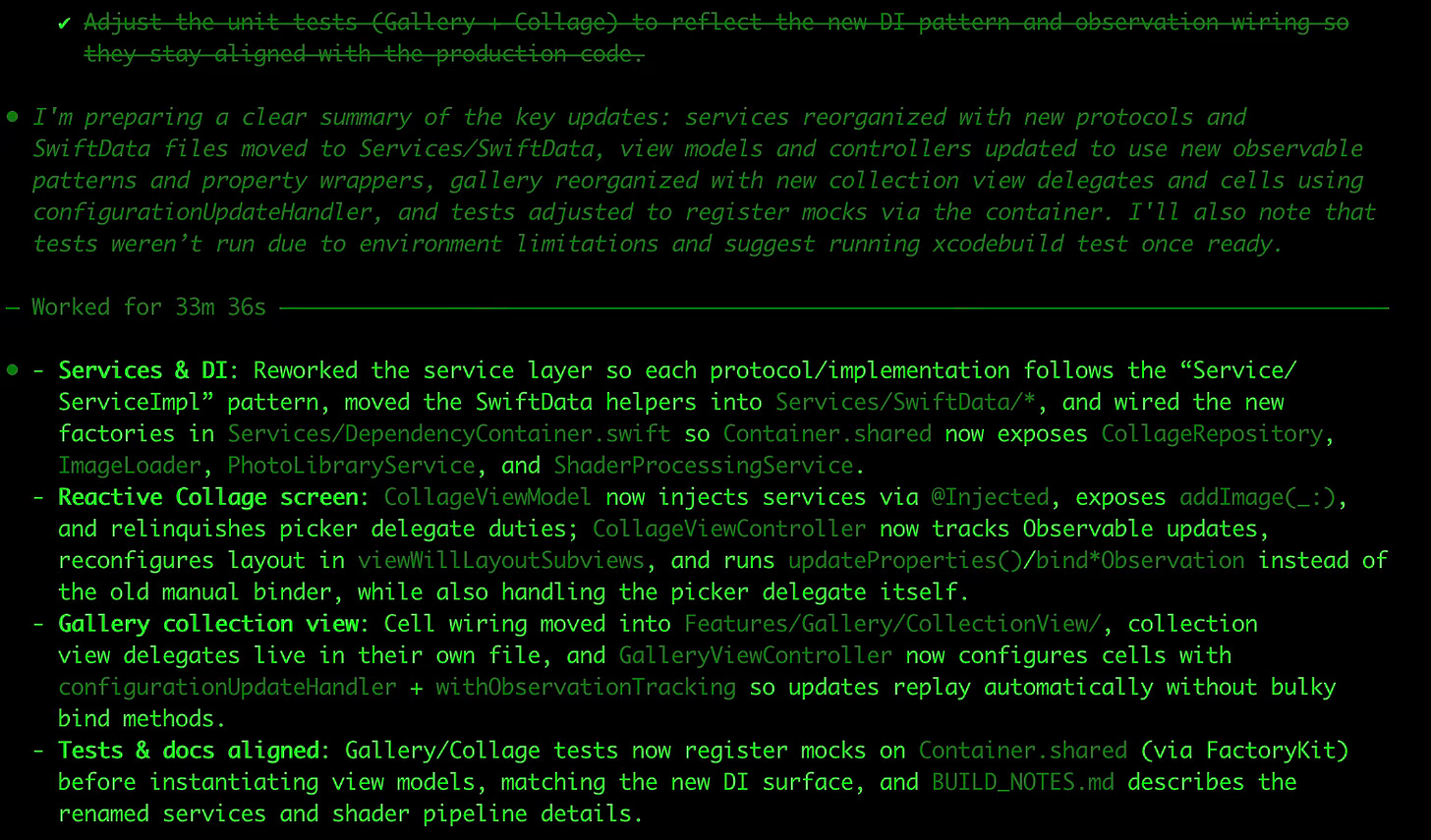

After your initial prompt, it’s really important to do a serious code review to catch anything you aren’t happy with.

Then you can let Codex rip autonomously for another 30 minutes.

This is pretty heavy early-project vibe-coding-between-Mario-Kart-races territory. In a serious project, you want to make small, incremental changes.

Any issues you catch can also go into an AGENTS.md file to help avoid the same mistake happening twice. I landed a lot of solutions to Swift 6.2 concurrency warning solutions in there.

I’m going to be very fair. It wasn’t all fun and games. I did run into teething issues with Core Image Metal kernels that I had to mostly solve manually. There were also a bunch of low-level styling issues like borders and symbol sizes that I wasn’t able to articulate clearly enough, and had to actually type out, like a 1337 Hacker in an 80s movie. But this is more a by-product of my perfectionism.

The big AI life-hack

Something I conveniently have access to: an enormous back-catalog of side projects and demo apps. This is the most significant timesaver when applying AI engineering, because you can simply point it at a folder and say “I want this feature, like it was done here, copy it”. Software engineering isn’t usually about remaking the wheel. It’s about plumbing together known solutions to create new utility.

Being able to reference existing work is, IMO, the main skill when using agentic AI to assist with engineering. It scales all the way up to big projects when you have a highly standardised codebase*.

*This is actually a thing, called Context Engineering.

I was able to utilise a bunch of reference code from previous projects I’ve worked on for the database, the shaders, and the Vision framework.

Falling back in love with UIKit

Hyper-responsive Gestures

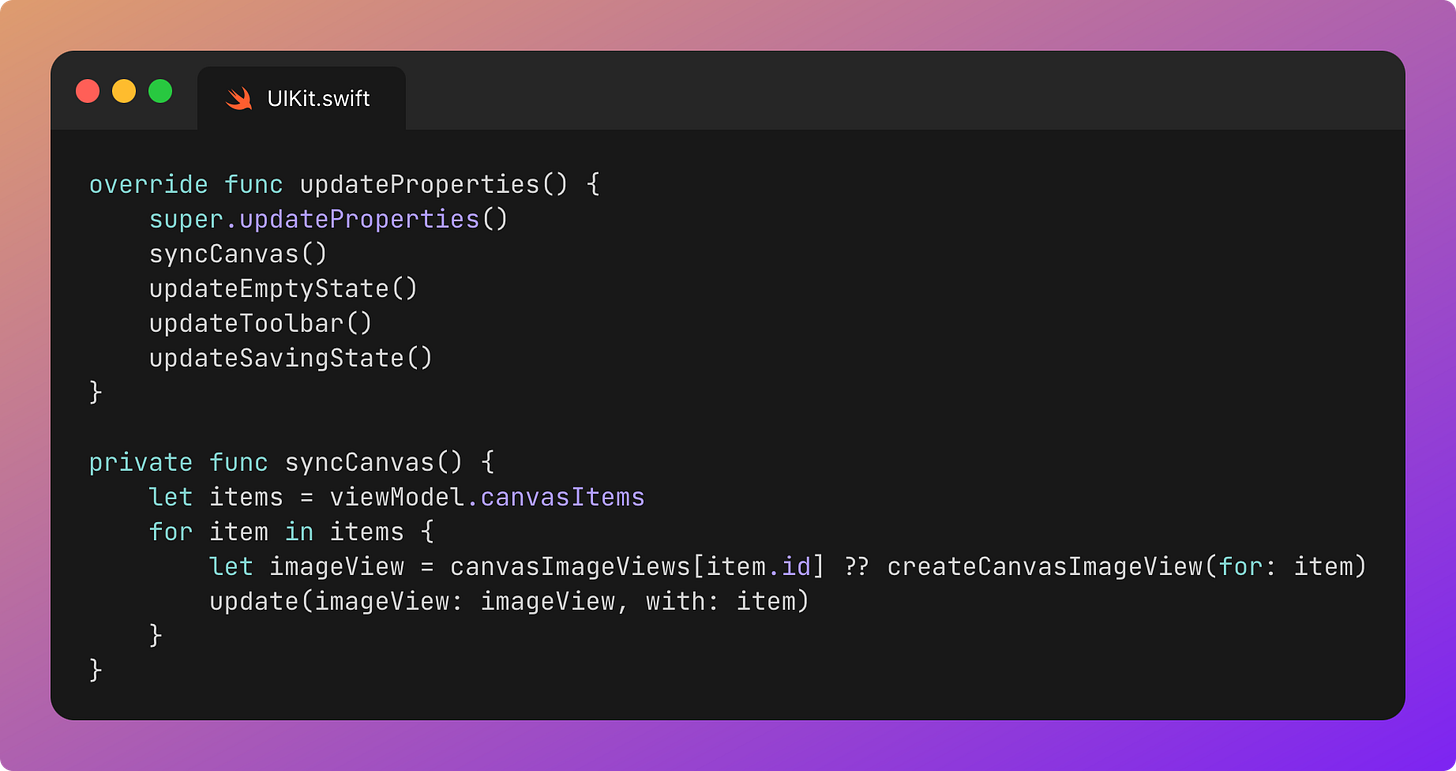

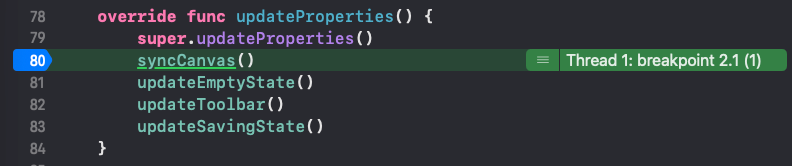

UIKit @Observable hooks allow the CollageViewController to listen for mutations in the view model’s canvasItems (containing each image, transformations, and shader modifications), and update subviews via updateProperties().

CollageViewController follows the standard MVVM single-source-of-truth, but unlike SwiftUI, we can short-circuit to get better performance.

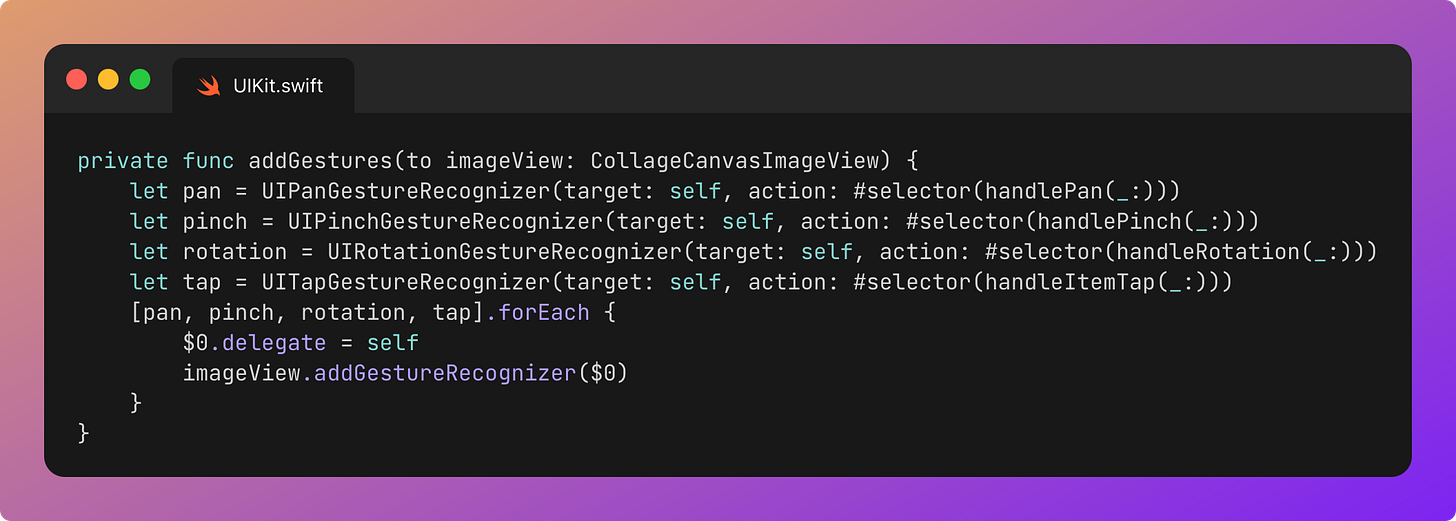

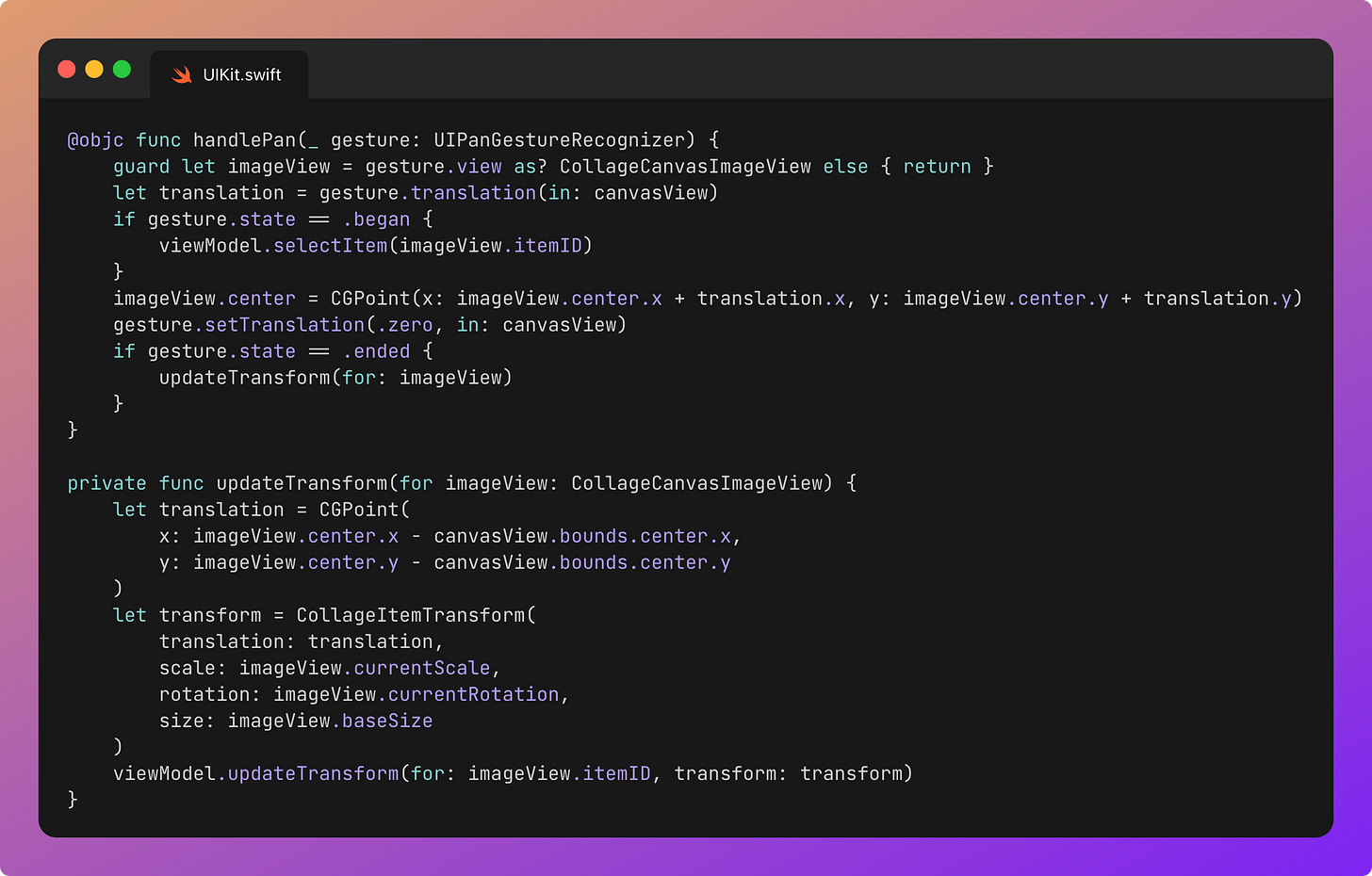

We’re adding various gestures to each image in our collage, imperatively.

When we apply one of these pan, zoom, or rotation gestures to an image node, we should see the UIView transform in real-time.

The gesture updates the @Observable view model to detail transformation parameters applied to each image node.

SwiftUI renders UI as a function of state, so each pinch, drag, or rotation on a @GestureState can trigger view invalidation, body diffing, layout computation, and a render pass. The UI waits for the state update pipeline to propagate back up to the pixels before it responds to the user. Frame by frame.

In UIKit, we could get the same beautiful, unidirectional flow by applying gestures to the relevant image transformation parameters on the @Observable view model. When this changes, updateProperties() will traverse each subviews and apply the transformations. CoreAnimation would only re-render each layer when its own properties change.

If we wanted to be extra efficient, we could even give each image node its own @Observable model, saving traversal across the subviews.

We can go even further and take a performance shortcut: directly apply gesture-based transformations to the UIViews in real-time, and withheld updates to the view model to the end of the gesture. This means we only hit updateProperties() on the view controller at the start and end of each gesture.

The ability to short-circuit like this is a big reason that UIKit is virtually always faster.

Ultra-controlled transitions

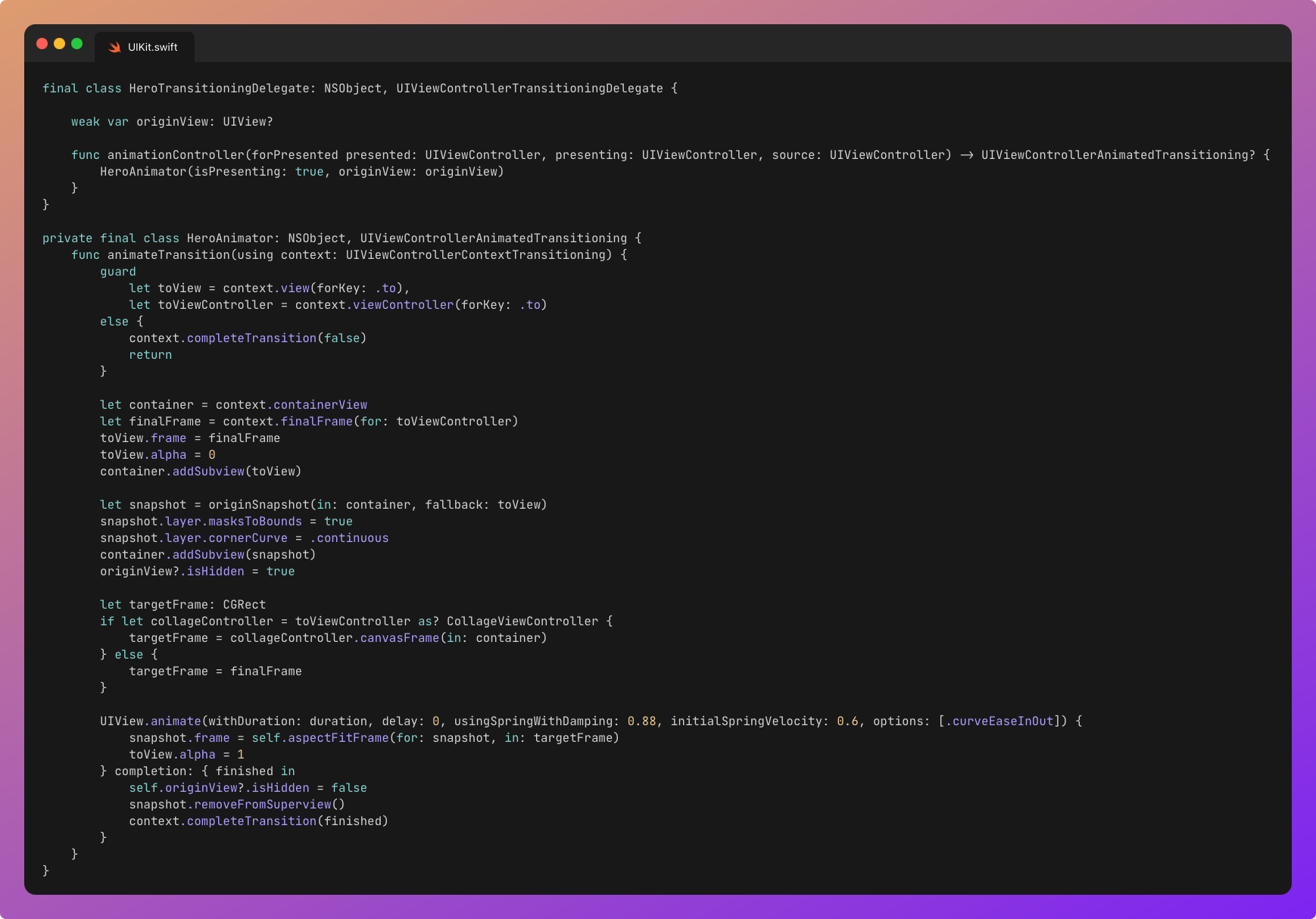

One final stop on our rediscovery tour is the hero animation, played when opening and closing a collage. It’s powered by UIViewControllerTransitioningDelegate. There’s a ton of imperative layout boilerplate here, which is extremely easy for an LLM to write. You simply provide the taste and tune the animation parameters.

SwiftUI has started to introduce hero transitions via NavigationTransition. This is welcome, but extremely basic and inflexible. It’s missing percentage-driven transitions, interactive transitions, and lacks the precision of custom animators for transitions.

Again, we scrape the surface of the UIKit iceberg.

Last Orders

I got beers with a friend recently, and we shared the same feeling. The Classic UIKit Stack™ just feels great to rediscover.

UIKit. Combine. Delegates. DispatchQueue (though, frankly, you’ll have to pry Swift Concurrency out of my cold, dead hands). All the classics. The gang, back together again.

SwiftUI was shipped from a place of fear, in response to the twin reapers of Flutter and React Native sucking developers out of Apple’s walled garden. Everyone jumped on the bandwagon, because suddenly we could knock out a complex screen in hours, not days.

Today, less code is hand-typed. Tomorrow, it will be less still.

Reading code is, again, the primary bottleneck to productivity.

AI-assisted engineering tools bestow speed without compromising maintainability, performance, and the all-important characteristic UX of iOS we know and love.

SwiftUI is dead. Long live UIKit.

I’m able to build anything, again.