How I Got Exploited At My First Startup

11 months in The Side Hustle From Hell

Being exploited by a startup is almost a rite of passage. I don’t think I can even call this a cautionary tale, because of what I took out of the experience.

Subscribe to Jacob’s Tech Tavern for free to get ludicrously in-depth articles on iOS, Swift, tech, & indie projects in your inbox every week.

Full subscribers unlock Quick Hacks, my advanced tips series, and enjoy my long-form articles 3 weeks before anyone else.

Gather ‘round, friends. This one has been a long time coming.

Grab a beer, we’ve got time 🍺.

This is a cautionary tale—one which left me scarred, jaded, and wiser. I hope that by reading this story, I can protect some of you from 11 months of pain.

The year was 2019.

My migration from academic overachiever to professional underachiever was an overwhelming success, as a slightly under-levelled junior at a big consultancy shop. But I couldn’t shake the feeling I was destined for great things.

I was engulfed by the daydreams many 24-year-olds experience when they stop being described as “precocious” and start spending their commutes listening to billionaires on podcasts. As my parasocial relationships to Peter Thiel and Reid Hoffman took hold, I was pretty sure I could become the next Jeff Bezos, or at least the next Drew Houston—I just had to execute well.

Enter: Fixr

The chance of a lifetime fell into my inbox through a friend of a friend of a friend. I was put in touch with Jimmy, the cofounder & Chief Financial Officer of a startup. His team was on the lookout for someone that knew mobile apps, to advise their startup and put out a few fires.

Involvement with a Startup.

In an Advisory Capacity.

If my weeks of tech consultancy training, and several years in mobile development, had prepared me for anything: it was this.

The venture was operating in stealth mode (if you don’t count the website), so Jimmy was cagey with the details until our initial call. I understood—as (probably) the next Zuckerberg, you need to be careful with your ideas around me.

We got on great. I briefed him on my credentials and showcased my passion for startups, and he told me I’d be a great fit for the team. It was a done deal. I’d taken the first step to fulfilling my destiny as the next great startup (advisor).

Fixr was the operating system for your car. It was the one-stop shop connecting you to qualified, vetted mechanics in your local area for anything your car needs—annual MOT, on-demand repair, and even roadside recovery.

Fixr had been operating for close to 3 years under a crack team of 3 part-time visionaries:

Jimmy (CFO) — an innovation manager at a consultancy

Kim (CMO) — a legal associate at an accounting firm

Mike (COO) — a mechanic

*I changed some names and obfuscated a few details outside the public domain; please simply imagine the cast of Better Call Saul. While you’re at it, feel free to picture me as Tony Dalton.

In a few short years, the team had an impressive collection of achievements:

Securing some startup capital to fund development, from a personal bank loan.

Winning a pitch contest at a local university.

Potential interest from VCs and accelerators, subject to getting traction.

Registering with the UK SEIS scheme; giving a tax break on seed investment.

Arranging a referral partnership, where we could get paid for convincing mechanics to switch banks.

Extensive market research, speaking to hundreds of mechanics, with nearly all of them expressing interest in joining the platform when launched.

Contriving a financial model demonstrating how £250k of seed funding will be transformed into £3M in revenue, with operations across Europe, by year 3.

A live static landing page, hosted on an AWS EC2 Medium server.

4 mostly-built apps for customers & mechanics, on iOS & Android.

Con-sultant

That final point was where they needed some expertise. Most of their bank loan runway had been burned on an overseas contractor they fired after 2 years, for incompetence. They switched to a Hyderabad-based agency, who were sanding off the rough edges and getting the 4 apps ready for launch day.

I met up with Jimmy for some casual in-person end-to-end testing of the near-finished product and… Oh boy.

One could say the app wasn’t quite production-ready.

In my advisory capacity, I was in charge of speaking to the agency and communicating the many, many, many bugs that remained. This is where I got my first taste of gaslighting from a client relationship manager whose job is to keep suckers on the hook.

“We agreed to the previous list of fixations only and never agreed anywhere as the part of the agreement. Please refer the email snapshot above.”

“Look at the specification. It does not specify anywhere we were asked to support screen dimensions larger than iPhone 4s sized.”

“The stripe payment integration is not of the phone application, you do not need this from us”

Things looked a little bleak with the late 2019 launch date, so I suggested to Jimmy perhaps I could help squash some of these bugs. The cofounders didn’t have access to the code repo, so I had to spend more time battling the relationship manager for access.

And eventually, I got it.

“Far, far below the deepest delving of FAANG and big consultancies, the world is gnawed by nameless devs. Even Bill Gates knows them not. They are older than he. Now I have walked there, but I will bring no report to darken the light of day.”

—Gandalf, a famous staff engineer

I saw only one way to bring Fixr to market.

We would need a full rewrite.

Co-flounder

Despite being £20,000 in the hole across 4 apps, the management team didn’t take much convincing to let go of a sunk costs. I whipped up a quick live-demo of a modern iOS map app, with custom photo location pin, plus an input form and photo capabilities.

In one Monster-and-Elvanse-fuelled night of passion, I was light years ahead of a build that had taken 3 years. They were sold.

In order to justify the extra time investment, I was provisionally brought on as cofounder and CTO. But we had a marketplace to build, and two platforms to serve. We needed an “Android guy”. I knew just the person: Gus.

Like me, he was keen on the idea, and in the market for a new side project. At a pre-lockdown party, I sold the dream: this product lives or dies via the traction we get in the next couple of months.

Dragging my good friend into the blender is a regret, but we kept each other sane through the subsequent 9 months.

Despite being late to the party, the team valued our potential contributions at 10% apiece—the level required to get into Y Combinator.

To make things official, and certify our equity stakes, Kim drew up contracts, which were quite obviously rehashed drafts of the contracts they gave the original ill-fated dev agency, plus a very spicy clause pertaining to equity shares.

The Management Team may terminate this agreement and reduce or fully remove the equity held by the Developer where the Development Services are not sufficiently met. This clause is to be carried out at the discretion of the Management Team.

I was about to sign, when Gus cleverly consulted his dad who, in a brilliant blaze of prescience, suggested we run a mile and block our teammates’ phone numbers. Gus and I knew better, and simply pushed the team to change the wording to “gross negligence”.

We were officially cofounders.

It was go-time.

The MVP

The prevailing months flew by in a COVID-tinged haze. While everyone else was baking bread and remunerating nursing staff via saucepans, Gus and I spent every free minute turning Fixr into a serious product.

Our weekly Zoom calls had a regular push-and-pull. Gus and I presented the latest flows. Kim and Jimmy praised our progress, while pushing to expand the scope. We had to add more features to win the market as a one-stop-shop.

Engineering busywork complete, we turned to our operators.

Kim shared her latest dream for our upcoming “viral marketing campaign” that would land thousands of sign-ups on launch day.

Mike spitballed when we might start to acquire mechanics. Perhaps we’d hook into local apprenticeship schemes once we had demand from customers. Achieving liquidity would be straightforward.

Jimmy went through his latest tinkering with the financial model—the cornerstone of our investment thesis—and talked us through the latest couple of emails from VC analysts who asked us to “get in touch when we had traction”.

This early traction would be everything.

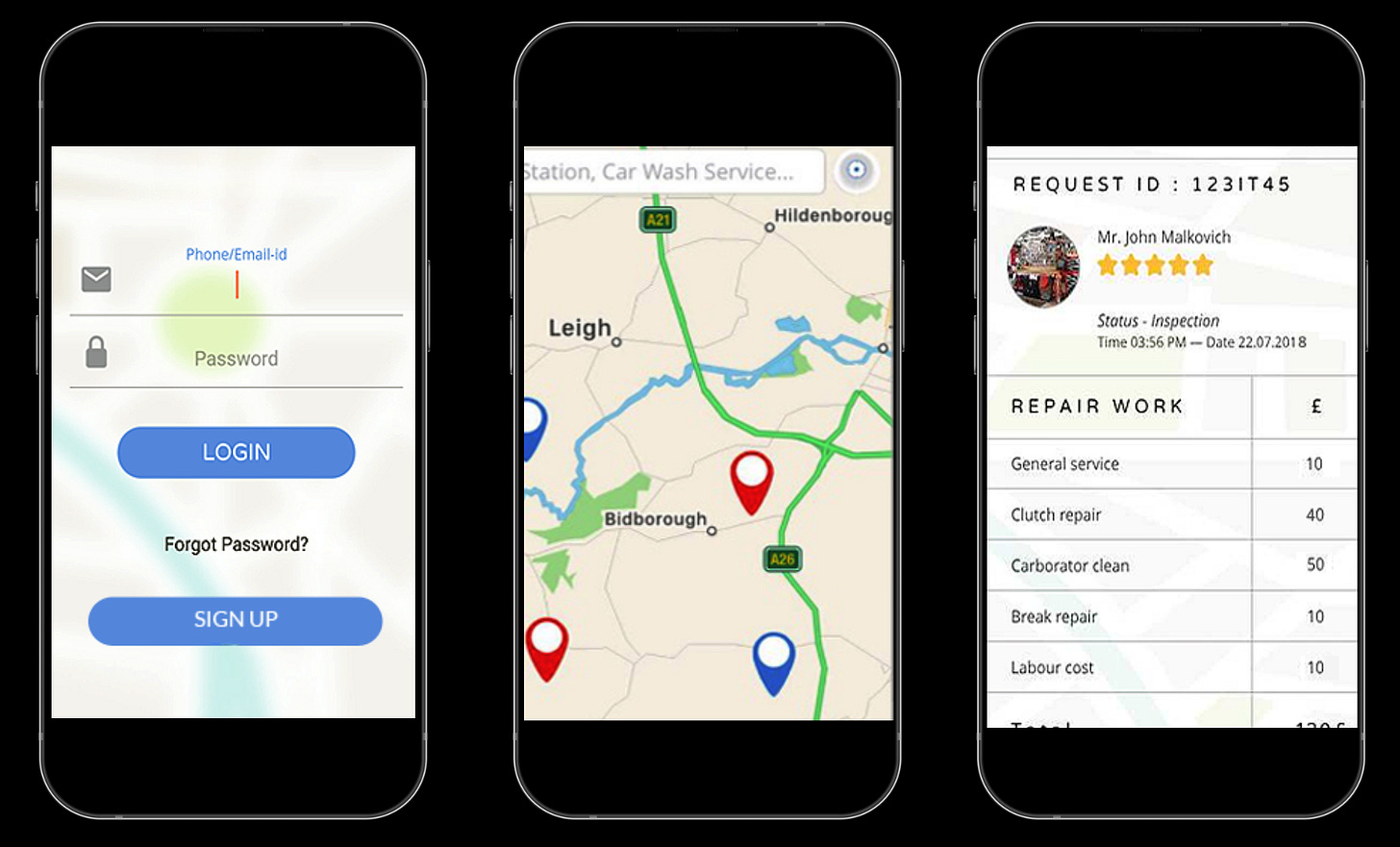

After months of neglecting our families, Gus and I had the MVP ready for prime-time, with a single robust user flow:

Users on the Customer apps can post local repair jobs. They can pay via the app and approve each invoice item during a repair job in real-time.

Mechanics on the companion app could bid for jobs, perform vehicle inspections, append work items during a job, and handle invoices automatically.

Fun fact, this project is how I cut my teeth on SwiftUI 1.0. The screenshots are lost to time (and dodgy source control), but the internal architecture was a hot mess.

Early UIKit inter-op was janky and it was difficult to pass state about. This was a problem when two of our major features used the Google Maps SDK (MapView didn’t exist!) and the camera.

A gigantic @EnvironmentObject singleton controlled the entire app state, and because NavigationView was so broken in SwiftUI 1.0, every screen transition was a modal.

This flow worked phenomenally, across our suite of 2 iOS apps and 2 Android apps. But it wasn’t enough for our cofounders. We had to have on-demand roadside recovery. We needed to include annual MOT checks. Flame decals are a must-have. Anything you need for your car, we had to be.

Failure to Launch

Gus and I noticed we actually had vertebrae, and pushed back hard.

Implementing their vision would take a full-time team multiple years. We had the MVP. We had to launch instead of spinning our wheels for another 3 years. Our cofounders had to stop dreaming and start operating.

Everything was ready to release in App Store Connect and the Google Play Store.

4 apps. One dream. Billions in potential.

We pressed the button. Release.

and…

Crickets.

Without any waitlisted mechanics, our imaginary viral marketing campaign was dead before it began. We had nothing on either side of our car repair marketplace for anything more than a tech demo.

Faced with the cold, harsh reality of zero users, zero revenue, and zero funding, Gus and I had a moment of clarity. We asked ourselves one question.

WTF had our cofounders been doing this whole time?

Trouble in startupland

It’s probably time to tell you that Jimmy and Mike despised each other. Jimmy didn’t respect Mike’s intelligence or commitment. Mike didn’t like Jimmy on a personal level. One of Kim’s primary roles in the business was as mediator between the two.

Unbeknownst to Gus and myself, our tidy 10% equity packages were mostly carved out of the hog carcass of Mike’s original third share. Jimmy, as chief visionary and de-facto CEO, had a capricious habit of unilaterally reallocating equity based on how much value he thought you brought to the table.

I was never in the room when these conversations happened, but Gus and I were immune to this chicanery—we’d negotiated our contractual protections up to “gross negligence”—a fairly high legal bar.

Gus’ dad is looking preeety smart right now.

The incompetence of the original dev agencies concealed a far deeper issue. The apps Gus and I hacked together? Not pretty. Worked brilliantly.

We were no longer sitting on a product problem, and the abject failure of the startup to achieve anything meaningful in 3 years no longer had anything to hide behind.

Always be hustlin’

I spent summer hustling to bail out the sinking ship:

I sat with Mike to reach out to mechanics and bootstrap our supply-side, trying to start at the town level.

I helped Kim to set up social media ads to bolster the demand-side, running campaigns in target towns to nurture local liquidity.

I wanted to go all-in: Jimmy offered to double my equity in exchange for co-signing to the business loan. Uhhh… I said I’d think about it.

I picked up some of the load of reaching out to angels, VCs, and business partners on LinkedIn.

This grind actually landed us a potential whale: a meeting with the CTO of RAC, one of the 2 big car recovery companies in the UK.

We pulled out all the stops to demo our product, impressing him with the simplicity and depth of the end-to-end repair flow from the mechanic side. Was this going well?

Astoundingly, Jimmy kept drawing attention to the £50-per-referral banking partnership we had arranged. Did he not realise they offer this to everyone?!

We staggered when asked about our sign-ups from mechanics (zero) and daily repair jobs (also zero). None of us had the presence of mind to request a more junior, less busy contact point.

Our collective—really, my, efforts—yielded nothing substantial. We didn’t have the demand to convince mechanics to sign up. We didn’t have the mechanics to supply any demand that might exist. Marketplaces are hard, it turns out. And we were not the team to build it.

I got a much-needed reality check at a post-lockdown family party. I enthusiastically gave my cousin the rundown on Fixr, talking him through our development process and my summer spent hustling. He simply asked, bewildered:

“Why are you doing all this work and not being paid?”

The Light at the End of the Tunnel

Come Autumn, things still weren’t going anywhere with Fixr.

Simultaneously, my underpaid mid-level consultancy role passed me up for promotion again. I wanted out, double-time.

I performed the reluctant ritual of reaching out to recruiters. On learning about my recent brush with startups, one recruiter suggested they had just the person to introduce me to.

Enter: Carbn. The app for building green habits and offsetting your emissions.

It was everything Fixr was not.

A bootstrapping first-time founder, a commercial strategist who could fund a full-time salary for the right cofounder and was very generous with our equity split.

He’d shopped around several ideas, validating a high-potential market niche in the US prepared to spend money on the product.

After this validation, he committed: £10k on a solid contractor for a full set of designs; shaping the early roadmap for our early product work and giving us a solid branding foundation.

The guy whipped out a rudimentary financial model in a few hours. Turns out it’s not that important—it’s for illustrating your runway and spending plan, not to justify an imaginary revenue number.

No clandestine activity with contracts. We hashed it out on SeedLegals over beers.

I tendered my resignation to my cofounders and relinquished my equity.

Gus quickly followed, immediately landing on his feet as an engineer in the banking sector. With no developers to keep the pretence of activity afloat, Fixr and the team soon dissolved.

What I learned from the experience

This was cathartic, but bloody hard to write.

The earliest draft of this article began on August 18, 2023. I wanted to do right by you, and waited until I could tell my story properly.

The temptation to annotate each paragraph with commentary was excruciating. But I wanted my naivety to speak for itself—I hope, by the end, you were also screaming “Get out! What are you doing!?” to both myself and Gus.

But do you want to know the terrible truth?

I loved every minute of it.

Like the intrepid doctor, the stoic investment banker, or the wily consultant, suffering is part of the package. I was in my element. I had my finger in every pie. I was doing a startup. I was executing, and for the first time in my professional life I wasn’t insulated from the results. I didn’t achieve my destiny of great things, but I’d built something.

My story is far from unique—being exploited by a startup is almost a rite of passage. I don’t think I can even call this a cautionary tale, because of what I took out of the experience. My hard-earned learning from Fixr opened another door to Carbn which I was uniquely qualified for.

If you’re early in your career (and childless), I would even go as far as to recommend a quixotic startup journey. As a 29-year-old developer, I’ve seen first-hand the compounding career benefits of side projects, in many of my colleagues and my friends.

Just watch out for some of the red flags which I summarised below!

Top 10 Red Flags

I wanted to end with a quick summary of some red flags you could encounter if you find yourself mired in a satanic side hustle.

If a startup has operated for a long time without launching, consider whether the team are serious. Even if you are all very driven, if your cofounders aren’t obviously A-players, your chances of outsized startup success are low (but you might still learn a lot).

If your equity share is contingent on being cut in on a business loan, you are being asked to invest your own money. Run.

If there is political infighting between cofounders, consider whether you want to raise funds and become legally bound to these people for several years.

There are 2 jobs at a startup: building and selling. If you aren’t sure what your cofounders are doing, trust your git instinct.

Building native on multiple platforms is an extremely inefficient allocation of resources when pre-product-market-fit. Building two apps on each platform is just mad.

Startup pitch competitions are mostly a waste of time—validation comes from talking to users and iterating, not from impressing a judge. This iterating is the hard part—everyone will tell you they like your app, and most will say they’d pay for it. Unless you have deep domain knowledge, talking to 300 technicians without a working product will not yield useful validation.

Did I mention that I never met Kim or Mike in person? COVID aside, nothing beats the magic of hacking side-by-side to bring your dream to life. It’s not a great sign if all your communication is remote.

Marketplace startups are often considered the hardest software startups to build, because you have to create two markets at once. They work best with frequent and inexpensive transactions (from which you can reasonably take a 20% cut).

When VCs tell you “talk to us again when you have traction”, they mean “if you prove there is a market opportunity and that you can execute as a management team, then we might consider you. But because I don’t believe either of those things will happen, I will not be taking a risk on you”.

It’s also a red flag if you aren’t vetted much yourself. If a company takes you on, consider if they want you based on merit, or whether you are the first engineer who agreed to work for free.

Thanks for reading Jacob’s Tech Tavern! I hope you enjoyed my story. 🍺

If you enjoyed this, please consider paying me. Full subscribers to Jacob’s Tech Tavern unlock Quick Hacks, my advanced tips series, and enjoy my long-form articles 3 weeks before anyone else.

I think this sounds like exactly the kind of failed frenzied early career experience that everyone should have. I had a similar one. Bravo on the write up, truly a right of passage into the world of startups and tech.

I have invested in few startups, being a part of 2 (out of 12 or 14). Some of them worked perfectly, some didnt and 2 were a scam. Robberies in white gloves.

Not to say anything bad about yourself, at least you received your lesson. Very valuable. Probably for life of investments and management.

Im so surprised you havent run earlier. Those founders were dreamers or lunatics rather. With some idea, dug out of the nose hole. Well done. Based on imaginary or profit-promised workforce. I met 2 such people in my past. Smooth talkers. Specialists in burning investors money.

Was so easy to make it working and basic level (you mentioned town level).

Anyways, good luck in your future and mind the time wasters, tire kickers and window lickers :)