Copy-on-write teaches you EVERYTHING about Swift Internals 🐮

isKnownUniquelyReferenced through the standard library, compiler, and runtime

There is a global function in Swift that, when you fully understand it, will teach you everything you need to know about Swift internals.

You’ll never guess what it is, because I guarantee you’ve used it less than 3 times in the real world, if you’ve even heard of it.

isKnownUniquelyReferenced().

If you know, you know: this function powers the copy-on-write optimisation (a.k.a. CoW, a.k.a.k.a. 🐮).

It pretty much only ever comes up if a) you’re a library author, or b) you’re interviewing someone and want to rate their power level when it comes to Swift internals*

*I never let interviews get to this point, because I burn 45 minutes responding to their first question about weak references.

I wanted to understand how this function worked, and little did I know that it would take me on an odyssey through every single layer and sublayer of the Swift source code. Seriously. Every layer.

As it happens, it’s pretty much the perfect candidate for doing this. type(of:) comes close, but doesn’t quite stick the landing in as satisfying a way.

Will learning all this make your hairline recede another inch? Yes.

Are you going to come on a fun journey to learn Swift Internals™? Also yes.

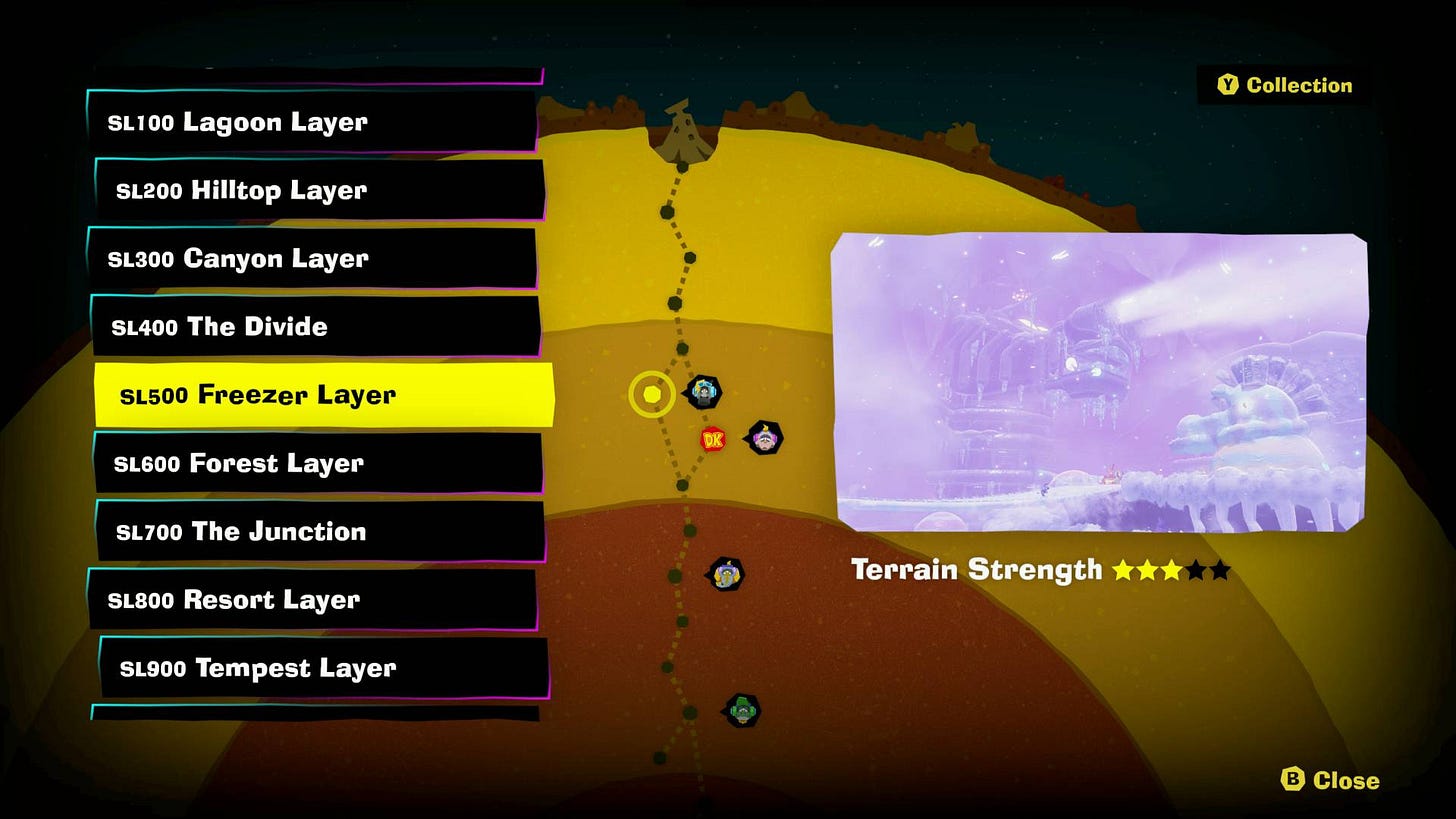

Let’s work through the various sublayers of the p̶l̶a̶n̶e̶t̶ Swift Source Code and discover once and for all how isKnownUniquelyReferenced works.

Journey to the centre of the 🐮

(yes we’re really going through all these)

What is 🐮?

For anyone who hasn’t brushed up on their interview prep recently:

🐮 optimises the performance of a Swift struct to get the best of both worlds:

easy-to-reason-about value semantics.

low memory overhead from reference semantics.

“Uhh, I just said I wasn’t doing interviews, can you not drop terms like “reference semantics” as if I remember what they are?” I hear you say from the future.

Right. Sorry.

Value and reference semantics

Value semantics = copies are independent entities

Reference semantics = copies point to the same underlying memory on the heap

structs that utilise 🐮 store their data in a memory buffer on the heap.

When the struct is copied, all the properties are copied, including the 64-bit pointer to the backing data, referencing the memory address 0x00000000d34db33f.

This is a shallow copy. Each copy of the reference still points to the same underling memory. This underlying memory is shared. This is reference semantics.

When the value of the data on a copy of a 🐮 struct changes, value semantics kick in.

The struct allocates a new buffer of memory on the heap, copies the updated data there, then points at the new buffer. A deep copy. It leaves the original memory block, and other instances of the struct pointing to it, unchanged.

🐮 In the Swift Standard Library

Many fundamental types in the Swift Standard Library utilise the 🐮 (copy-on-write) optimisation:

Data (actually an impostor from Foundation, but it’s one of the gang).

When using these data structures in your code, or even types that contain them, you reap the benefits of the underlying 🐮 optimisation for free.

But it’s possible to implement 🐮 in your own types, too!

Implementing 🐮

Very senior iOS engineers will tell you how you can implement your own types that utilise 🐮. Check out this sample robbed straight from Apple’s Swift Optimisation Tips:

In short, you place your struct, T, in Box.

Box wraps T in a reference, Ref, placing the structure on the heap.

You can read the value inside Box trivially.

When you write the value, we check if the memory inside Ref is uniquely referenced, that is, if there is only one pointer to this instance. If it is unique, the value mutates in-place. Otherwise, the heap memory buffer under Ref is copied into a new address before mutation. The Ref pointer inside Box changes to point to this new address.

This illustrative example shows how isKnownUniquelyReferenced can be used to implement 🐮, but it’s kind of sh*tty for real life code: you’re polluting your type with slower reference access semantics to make copying a bit more efficient.

It’s only a good idea when copying is expected and there is enough memory that it makes sense to place it on the heap.

A mysterious function, isKnownUniquelyReferenced, is the secret sauce that makes this optimisation possible.

As it turns out, it’s fucking mysterious, because I originally spent about 3 weeks traversing megabytes of C++ (in 2023, before AI tooling could even touch this kind of task) to understand what the hell it was doing.

The Swift Standard Library

First things first.

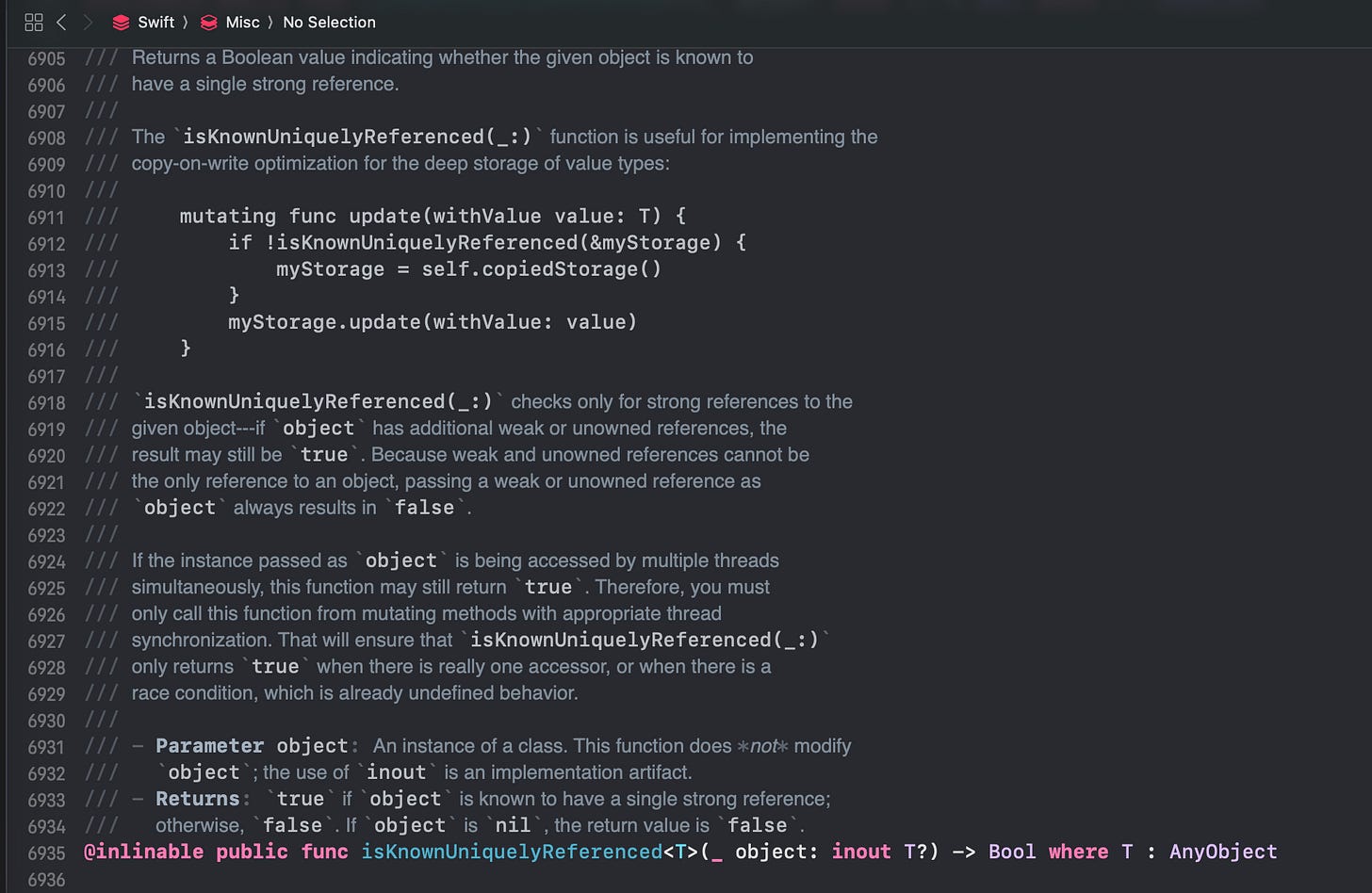

Let’s download the Swift source code, search for isKnownUniquelyReferenced, and take a gander at the implementation.

Or, you can just CMD+Click that bad boy in Xcode.

It’s holed up in ManagedBuffer.swift, underneath the definition of ManagedBufferPointer. I don’t love putting global functions in the same file as semi-related data structures, but who am I to question the wisdom of our Cupertinoverlords?

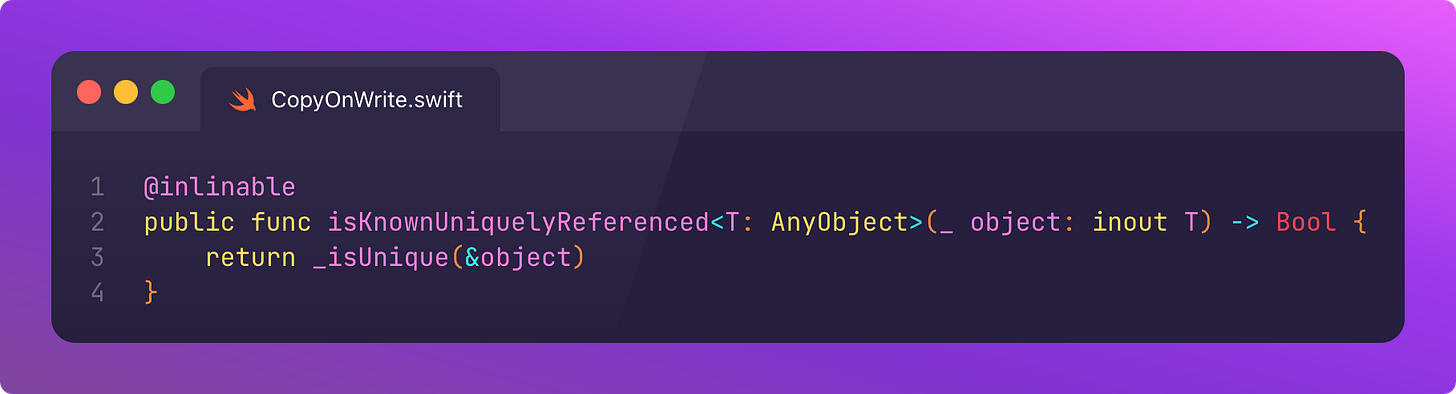

Here’s the implementation of isKnownUniquelyReferenced I’ve been searching for in all its glory:

All in a day’s work.

I’ll head to the pub now for a well-deserved beverage.

Builtins

I’ve got my beer!

Uh, I suppose I don’t have much else on.

Perhaps we can dive a little bit deeper and find out what _isUnique is doing.

Much deeper. Including Builtins, The Swift Compiler, The Abstract Syntax Tree, Swift Intermediate Language, LLVM Intermediate Representation, The Swift Runtime, SwiftShims, and The isKnownUniquelyReferenced Meme.

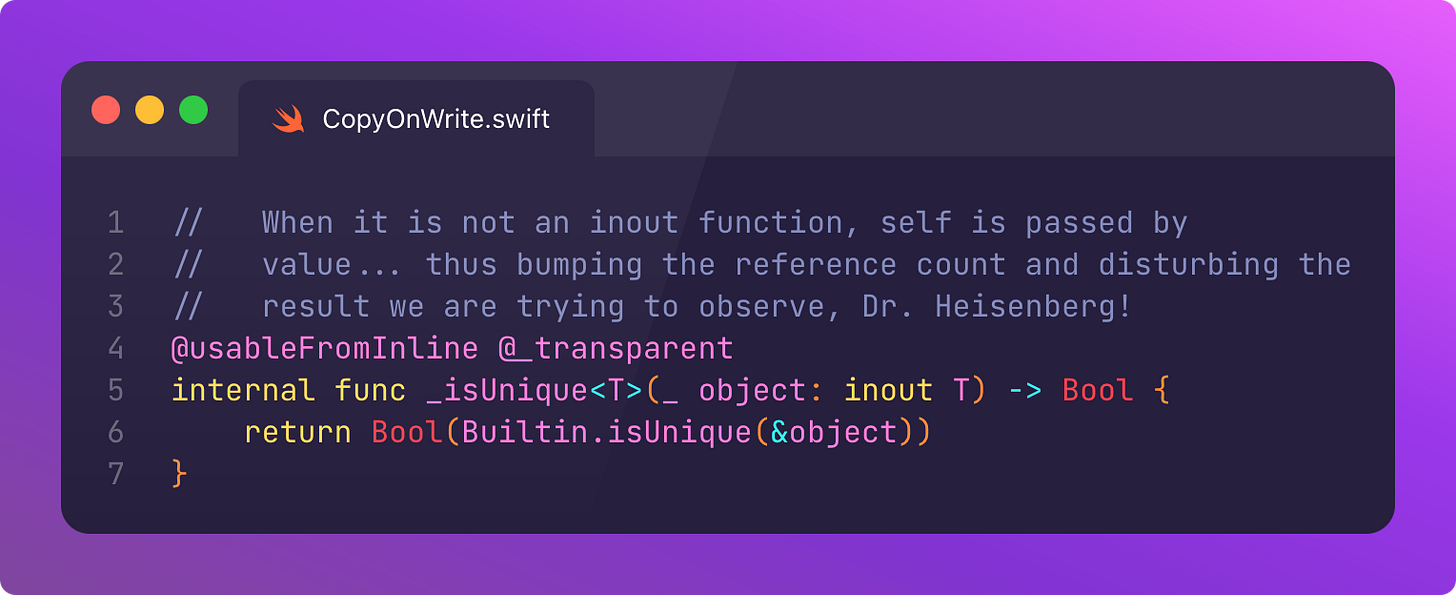

We find _isUnique defined pretty close by in Builtin.swift:

Loving the doc comments from Apple; let’s as an industry strive for more quantum physics references in our source code!

We need to find out what this Builtin.isUnique(&object) guy is trying to do.

This is where things get interesting.

We find this Builtin function defined somewhere totally different: Builtins.def.

BUILTIN_SIL_OPERATION(IsUnique, "isUnique", Special)Why is this located in include/AST? What is a SIL operation? Huh???

Before we can progress any further, we need to understand a bit of theory about the Swift Compiler and its dad, LLVM.

(Interlude) The Swift Compiler

The Swift Compiler processes Swift source code files into efficient machine code. It’s a pipeline with several Swift-specific optimisation stages.

Let’s get our heads around each step in some detail:

.swiftfiles are parsed and turned into a data structure known as an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), making it easy for algorithms to traverse.Semantic analysis is performed on the AST, performing tasks such as type-checking, evaluating protocol conformance, and checking variable scopes.

Swift Intermediate Language (SIL) is generated from the AST. This is a halfway point between raw Swift code and the low-level LLVM machine code.

This SIL is optimised through various passes. ARC is optimised, generics are specialised, code is inlined, and devirtualization replaces dynamic dispatch.

Optimised SIL is transformed into LLVM IR (Intermediate Representation). This is a high-level, language-independent kind of assembly language.

LLVM is a compiler toolchain: a frontend that processes any language into IR, and a backend that translates IR into machine instructions for any CPU. LLVM runs multiple optimisation passes on IR, enhancing performance for the target CPU.

The LLVM backend transforms the LLVM IR into actual machine code and produces object

.ofiles. These contain these assembly instructions, metadata, strings, and debug information.In the final compilation step, the Linker combines various object files with libraries into a single executable, which the OS can load to run a Swift application.

I go into way more detail here:

The Swift Compiler

·The Swift language was created by Chris Lattner. Before he ran the Xcode and compiler teams at Apple, he built LLVM at age 23. That’s right. Chris is pretty much Impostor Syndrome: The Movie.

Our isKnownUniquelyReferenced Compass

With that substantial segue completed, let’s return to our isKnownUniquelyReferenced deep-dive.

Now that we understand how the Swift Compiler works, we have a compass with which to orient ourselves while we dredge the depths of the Swift source code.

Instead of inspecting the 859 individual instances of isUnique we find when we CMF+F the Swift codebase, we can:

Find out how the isUnique Builtin function is applied to the Abstract Syntax Tree.

Work out how isUnique looks when it is transformed into SIL (Swift Intermediate Language).

Determine how isUnique behaves when converted to LLVM Intermediate Representation.

Understand how these low-level instructions check whether an object is uniquely referenced.

(I didn’t know this at the time, but this only took me halfway).

The Abstract Syntax Tree

Last time we left off, we found the Builtin declaration for the isUnique method in the AST/ folder, Builtins.def:

/// isUnique only returns true for non-null, native swift object

/// references with a strong reference count of one.

BUILTIN_SIL_OPERATION(IsUnique, "isUnique", Special).def files contain exported C++ macro definitions. Think of them like header files.

The include/ folder defines a public interface to the Swift Compiler, which is made available to stdlib/, the Swift Standard Library.

Builtins on the AST

First, we need to work out how the Builtin isUnique function gets applied to the Abstract Syntax Tree.

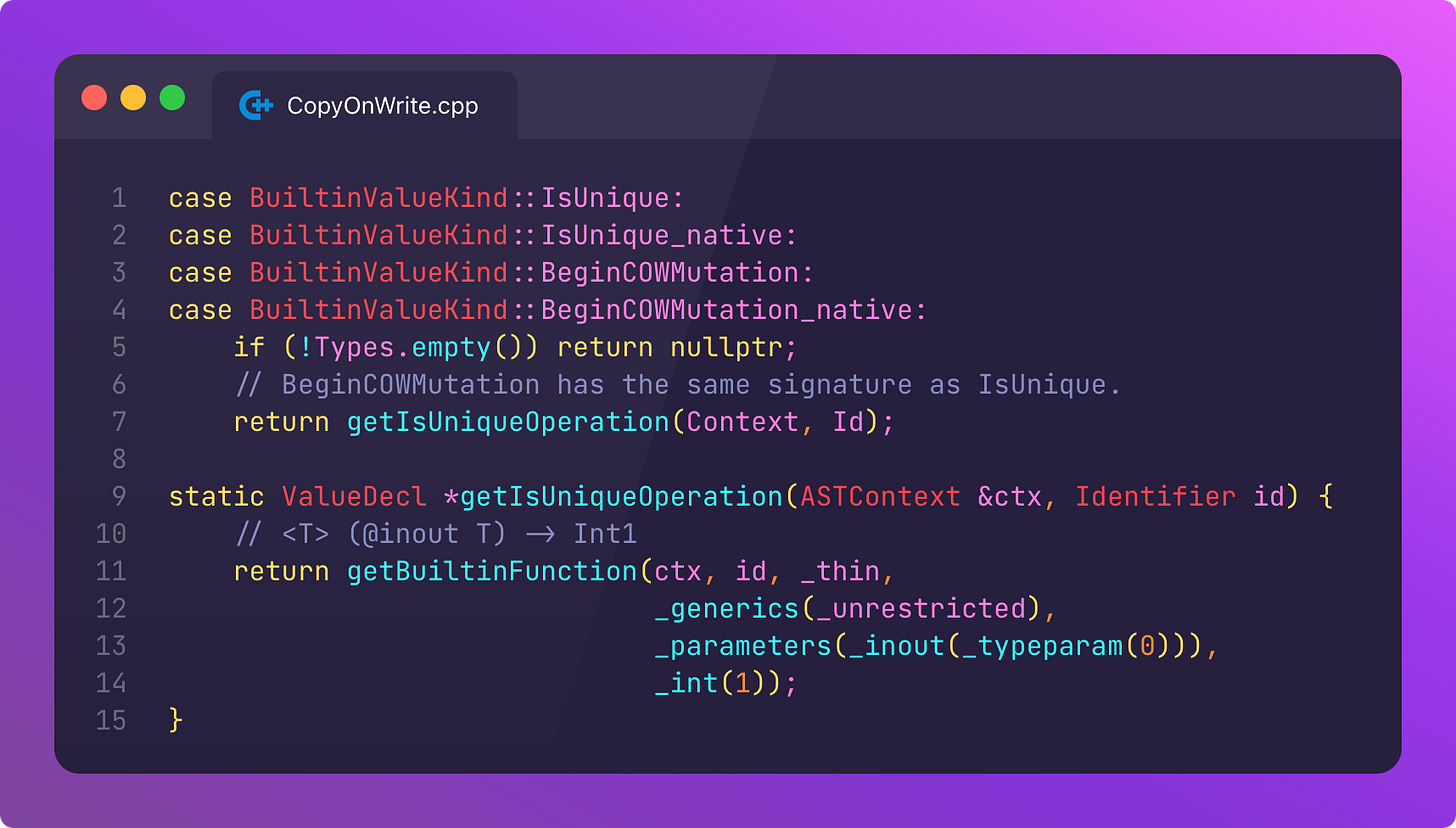

We find the Builtin being synthesised here in Builtins.cpp:

Several methods show up here: IsUnique, IsUnique_native (with extra safety checks), and BeginCOWMutation, which the Swift Standard Library uses to internally implement 🐮 for Array, ArraySlice and ContiguousArray.

These variants all produce the same getIsUniqueOperation, hung like so many baubles onto the AST (abstract syntax tree). This itself calls getBuiltinFunction to return a pointer to a ValueDecl, which represents a function signature.

You’ll notice the function signature returns Int1, a single-bit Integer. This is actually the underlying “Builtin” backing store used to implement the Swift Bool!

Synthesising a Builtin Function

getBuiltinFunction is actually implemented in this same file:

With most code samples in this article, I’ve stripped out most of the code to make the key moving parts clearer, but feel free to look at the full source yourself. There’s still a whole bunch of code, so I apologise for my crappy redaction.

There are 3 critical steps to follow here:

A reference to the Builtin module is retrieved from the ctx, the AST context, a repository of shared information the compiler uses to generate functions.

The generic inout parameter for isUnique and the result type, Int1, are defined here, to synthesise the signature of the FuncDecl.

id, the Builtin function identifier, is used to synthesise the function declaration we want from the Builtin module, i.e. IsUnique.

In summary, a FuncDecl, a function declaration, is synthesised. This implements the isUnique method on the Builtin module, and gets hung on the Abstract Syntax Tree.

All this processing allows Builtins to behave just like regular Swift functions.

The Builtin Module

Swift’s Builtin module itself contains a set of low-level functions and operations that map to LLVM IR instructions, bypassing Swift’s ordinary type safety mechanisms.

As we have seen, Builtins are used extensively in the Standard Library for performance, but Apple doesn’t trust us mere mortals to utilise them ourselves.

To be honest, I’m 2 Hepcats deep at the pub, and I wouldn’t trust me either.

AST Recap

Let’s recap on our progress so far:

isKnownUniquelyReferenced calls an internal isUnique method, which uses a Builtin method, a special low-level function implemented inside the compiler.

When Swift code compiles, Builtin.isUnique plops straight onto the AST. Indistinguishable from a run-of-the-mill Swift function. Later compilation stages treat it as such, but ultimately it maps to a dedicated instruction.

What happens to this Builtin function next? How does the resulting low-level instruction check the reference count?

To truly find out, we need to go deeper.

Let’s check our compass.

Next stop?

SIL.

Swift Intermediate Language

After constructing an Abstract Syntax Tree and synthesising Builtin function declarations, the Swift Compiler converts your code into Swift Intermediate Language. SIL is the precursor to LLVM IR, which itself undergoes multiple very cool Swift-specific optimisation passes.

In our journey to find out how the isUnique Builtin is working, the obvious first port of call is the SIL Generation library, and specifically, SILGenBuiltin.cpp. It’s not easy to find the right function calls. Naming is a bit jank between compiler steps.

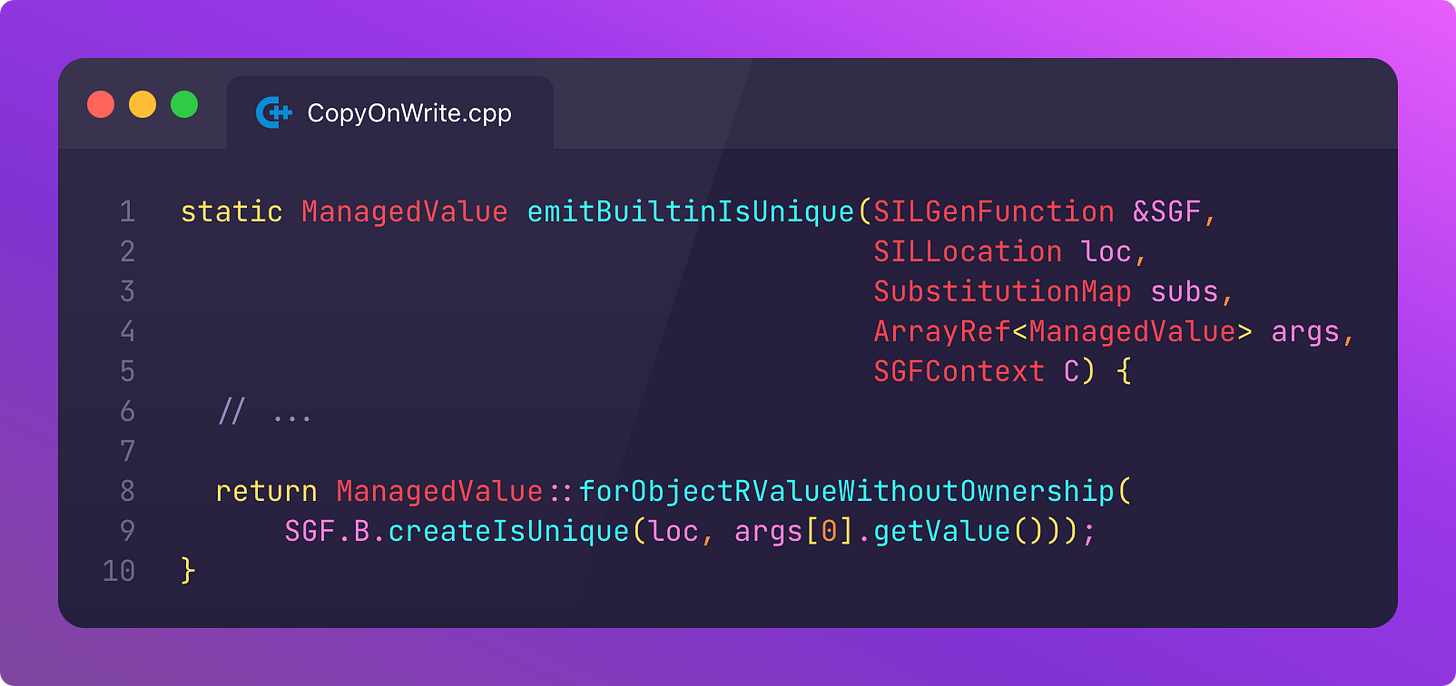

This function looks… about right:

Only 10 lines this time. I’m learning. As before, I’ve left out numerous lines of C++ assertions (mostly nullability checks) to make the code easier to follow.

This emitBuiltinIsUnique method, naturally, emits the SIL instructions for the Builtin function isUnique.

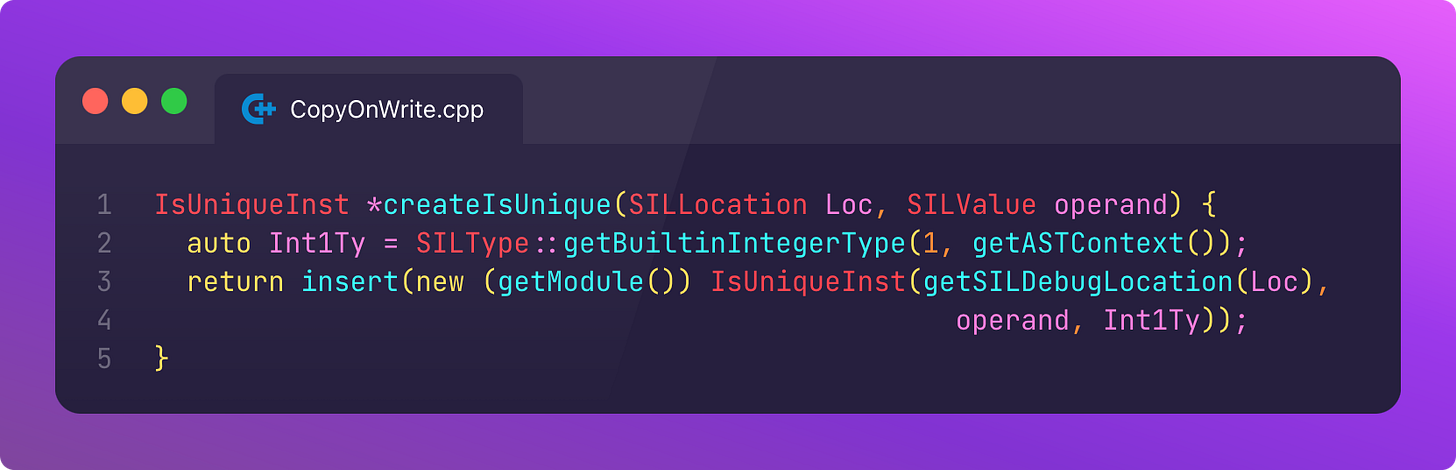

Following createIsUnique further, we find it defined in include/ inside SILBuilder.h, which acts as the public interface for SIL:

C++ header files often inline their methods. createIsUnique method, in arcane C++ syntax, instantiates an instance of the type IsUniqueInst. Inst, in this context, meaning instruction, not instance.

Uh, perhaps I structured the above paragraph pretty badly.

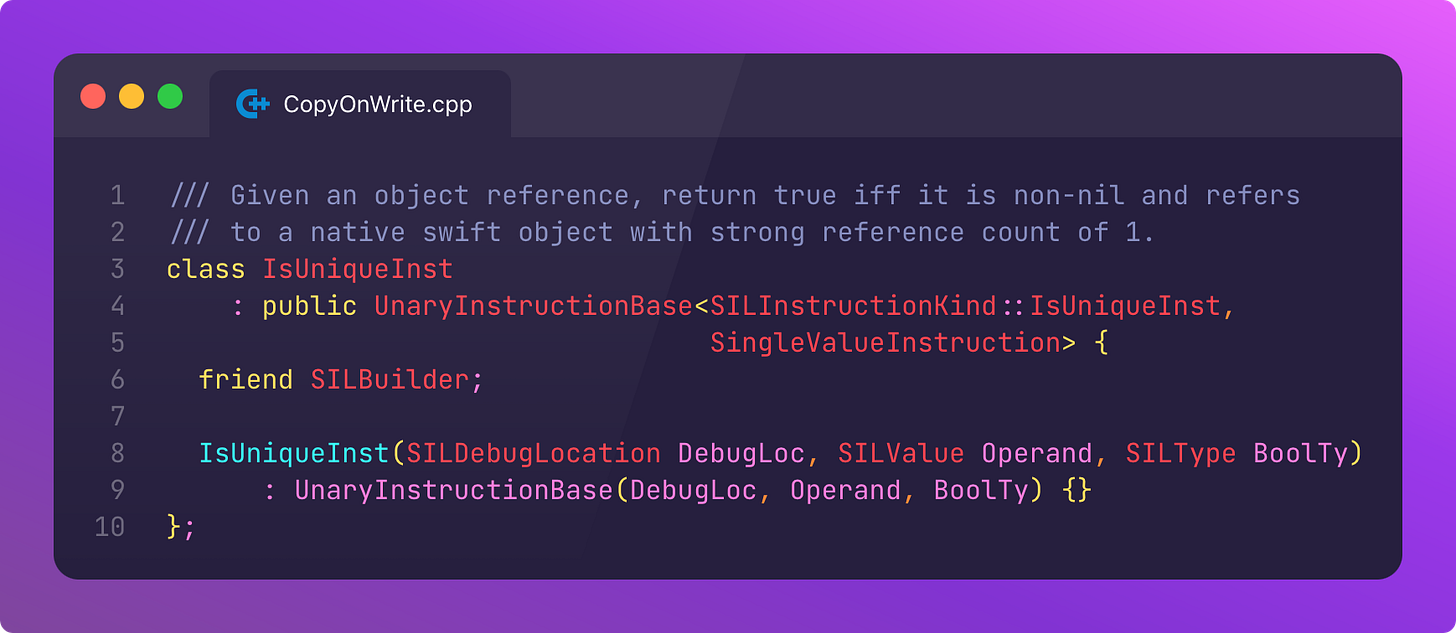

We locate the class declaration for IsUniqueInst at SILInstruction.h:

IsUniqueInst ultimately defines the Swift Intermediate Language instruction, which checks whether an object on the heap is uniquely referenced. This SIL instruction is now ready for optimisation passes and eventual conversion into LLVM IR.

Desperate to learn more about Swift Intermediate Language? Check out my O.G. Elite Hack, my first every foray into paid content, where I go way deeper on what it does for Swift.

Swift Intermediate Language

·The Swift Compiler is a mysterious multi-headed hydra. It takes your code through a many-step journey from hello world to machine code:

Let’s make this simple: we haven’t worked out how the uniqueness checks are happening yet.

The key to searching through the compiler is all about maintaining your bearings as you traverse each layer, down towards low-level instructions and runtime ABI calls. Usually, the runtime that has what we’re looking for. We’ll get to that, bear with me.

LLVM Intermediate Representation

Chris Lattner, creator of LLVM and Swift, apocryphally called Swift “syntactic sugar for LLVM.”

After parsing the Abstract Syntax Tree and Swift Intermediate Language generation, we arrive at the lowest level of the Swift frontend to LLVM: Synthesising instructions in LLVM Intermediate Representation.

LLVM IR is a language-independent, high-level assembly language around which LLVM itself is designed. The LLVM toolchain optimises this IR for any CPU instruction set architecture you want to run your code on.

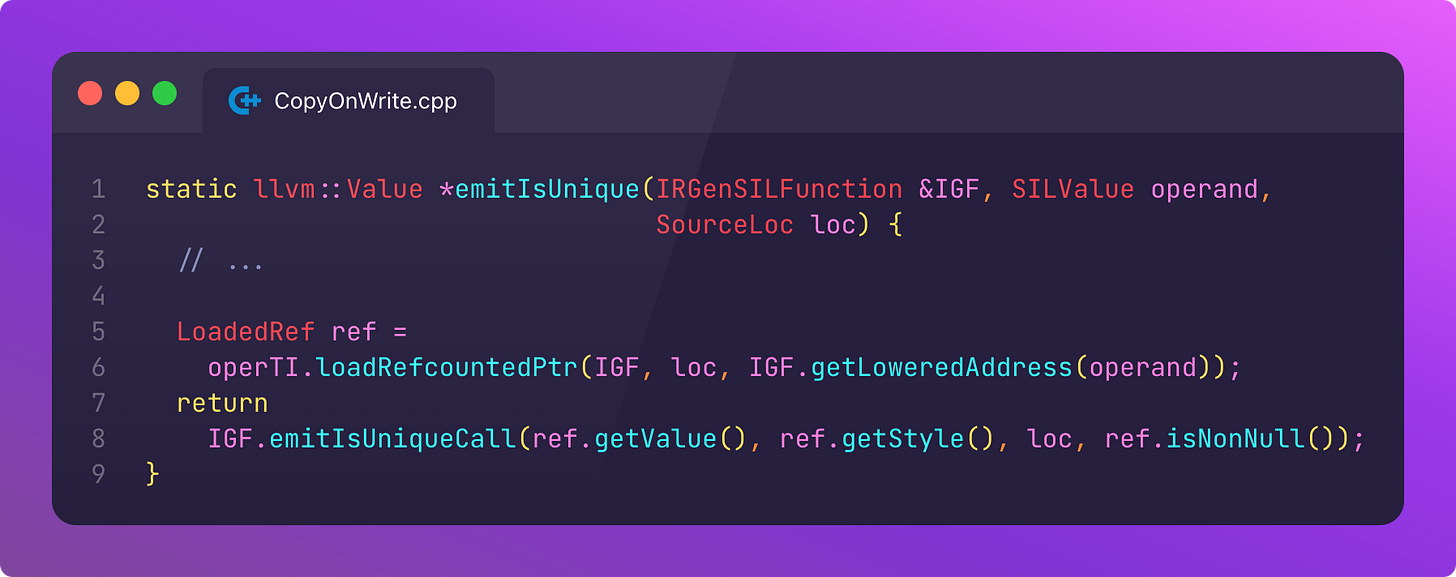

After searching through lib/IRGen/, the library for generating LLVM IR, we spot a familiar-looking declaration in IRGenSIL.cpp: this time, taking in an SIL instruction as an argument and emitting LLVM IR for the isUnique Builtin function:

This method loads in a “reference-counted pointer”, that is, a pointer to the object we’re checking the uniqueness of, in loadRefcountedPtr. Then it emits the isUnique function call as an LLVM IR instruction.

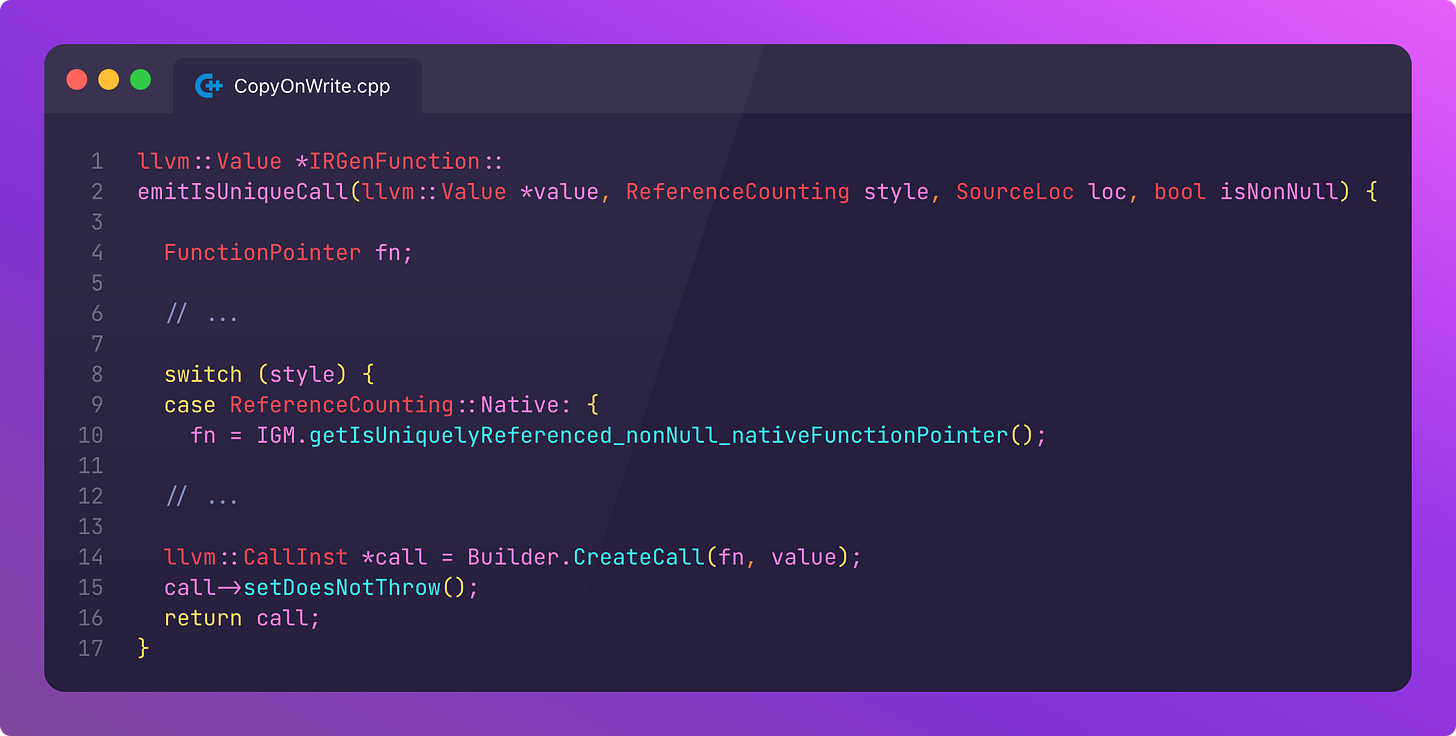

Following this emitIsUniqueCall function call along; we are led to GenHeap.cpp in the IRGen/ library.

The documentation at the top of the file reads:

“This file implements routines for arbitrary Swift-native heap objects, such as layout and reference-counting.”

Is that light I see at the end of the tunnel?

Let’s read through the implementation of emitIsUniqueCall:

I’ve omitted a ton of code here, mostly around switch cases for nullables and ObjC.

The getIsUniquelyReferenced_nonNull_nativeFunctionPointer() function call generates LLVM IR, which, when compiled and linked, calls into the Swift Runtime™ upon execution.

It looks like our understanding of Builtins was a little incomplete.

This is really important, probably the most important bit so far:

Builtins usually represent low-level, memory-unsafe, hyper-efficient types like Builtin.Int1, Builtin.Int64, and Builtin.FPIEEE64 (a.k.a. “Double”). Stdlib structs like Bool and Int use these as internal backing storage.

But Builtins can also function as direct Swift runtime calls. The functions compile directly down into instructions that call into the runtime library.

This is all possible due to the incestuously interlinked nature of Chris Lattner’s Targaryen harem: The Swift Standard Library, the Swift Compiler, and the Swift Runtime.

The Swift Runtime

The Swift Runtime provides core functionality you need to execute a Swift program: Dynamic dispatch, error handling, types, and memory management operations like reference counting.

I think you can see where this is going, at last.

If you like runtimes, but aren’t sure you’re ready to love runtimes, here’s an excellent primer:

The Swift Runtime: Your Silent Partner

·The Swift Runtime, a.k.a libswiftCore, is a C++ library that runs alongside Swift programs to facilitates core language features. I set out to understand what we mean by “runs alongside” and “facilitates core language features”.

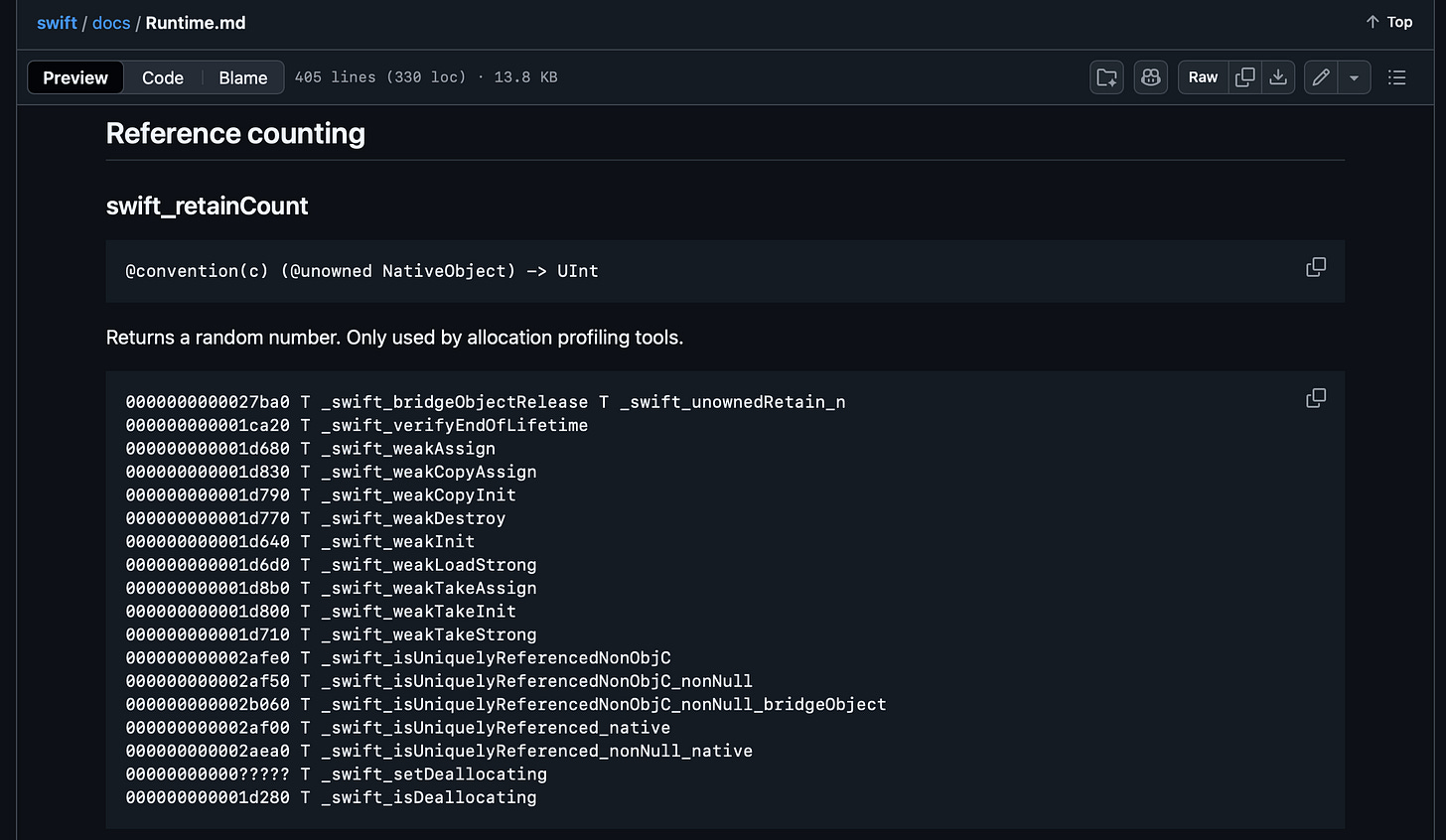

Checking the docs

Let’s investigate where the LLVM IR instruction for IGM.getIsUniquelyReferenced_nonNull_nativeFunctionPointer actually ends up.

This is more art than science: naming is fabulously inconsistent between Swift layers.

Like all good engineers, we can save ourselves hours of flailing about with a few minutes of reading documentation.

The Swift Runtime ABI documentation defines the interface that compiled machine instructions may call into. Specifically, the memory offset for each function inside the compiled runtime binary.

I’ll do an article on ABI stability once I’m convinced lots of people will pay for it, because I am not touching that sh*t for free.

The definition we’re looking for is _swift_isUniquelyReferenced_nonNull_native:

Fortunately, we don’t need to search out 000000000002aea0 in some obscure binary.

Unfortunately, we do have quite a bit more C++ to sift through.

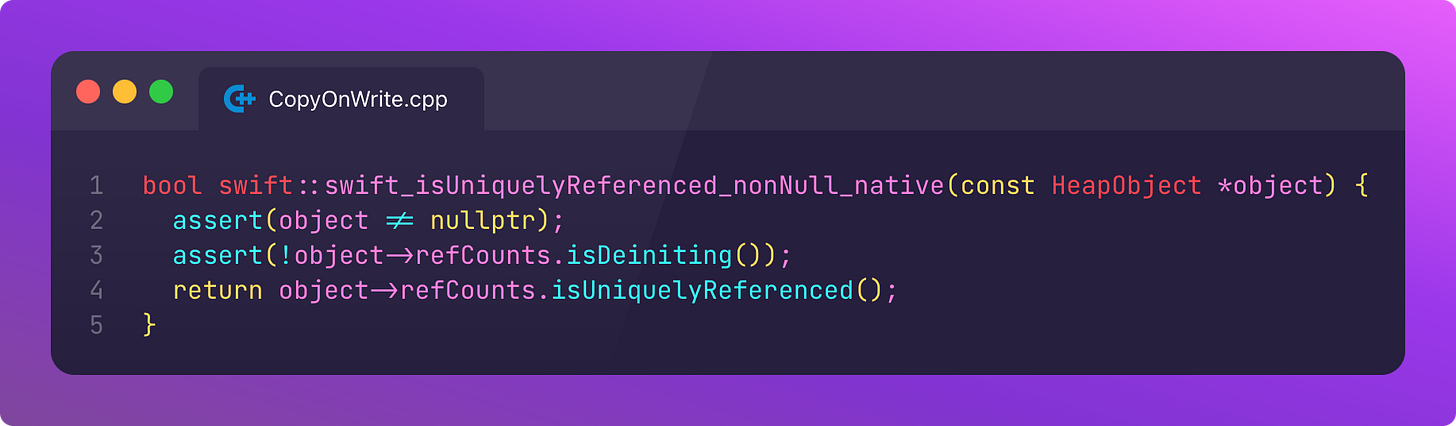

Swift Object

I investigated the Swift Runtime source code in /stdlib/public/runtime.

Looking at SwiftObject.mm (an Objective C++ file!), we locate the function that was defined in the ABI:

After some assertions to avoid undefined behaviour from null pointers (no type-safe nullability here!), we are looking at the HeapObject argument, inspecting its refCount property, and asking if it’s uniquely referenced.

HeapObject

Every reference type in Swift stored in a block of memory on the heap. HeapObject represents the “header” metadata attached to each of these blocks of memory, stored contiguously in front of the memory itself, like so:

+-----------------------+

| HeapObject | <- header struct

| - metadata (isa) ptr | <- type information

| - inlineRefCounts | <- reference count bits

+-----------------------+

| Instance Data | <- The actual data for your object

| - field1 |

| - field2 |

| - ... |

+-----------------------+HeapObject is a simple C struct storing type metadata and reference counts. RefCounts is, itself, a struct that holds the strong, weak, and unowned reference counts of the object in memory.

Uh, I also did a ridiculously in-depth deep-dive into reference counting here. Like, I literally look at the bit layout of the refCounts C struct. It’s good, clean fun.

Bits & Side Tables: How Reference Counting Works in Swift

·Every iOS dev has a soft spot, or perhaps a weak spot, for Swift reference counts. This stems from the fact that we've all survived countless interview questions about it:

Like SEAL Team 6, let’s target where isUniquelyReferenced() is implemented, on the refCount for a HeapObject. With extreme prejudice.

SwiftShims

SwiftShims is a lightweight compatibility layer between the Standard Library, the Runtime, the Compiler, and the OS. This collection of C and C++ header files helps to bridge high-level code with underlying system libraries.

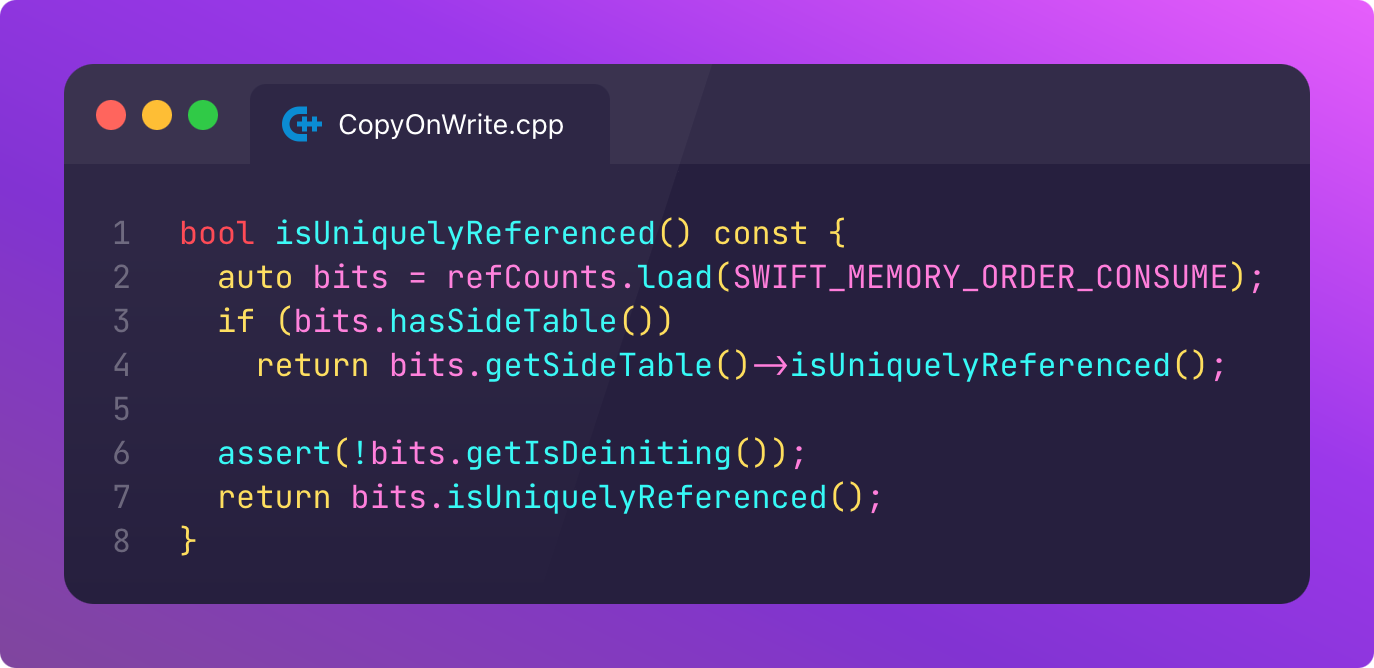

Critically, RefCount.h implements the method we’re tracking down:

This refCount struct has an isUniquelyReferenced() property. For this uniqueness check, we safely load the memory into the bits property and ask if it’s uniquely referenced.

If the object has any weak references (or the strong or unowned ref counts overflow), the refCounts live on a “side table”. That’s why the isUniquelyReferenced() check either loads directly from refCounts or checks the side table.

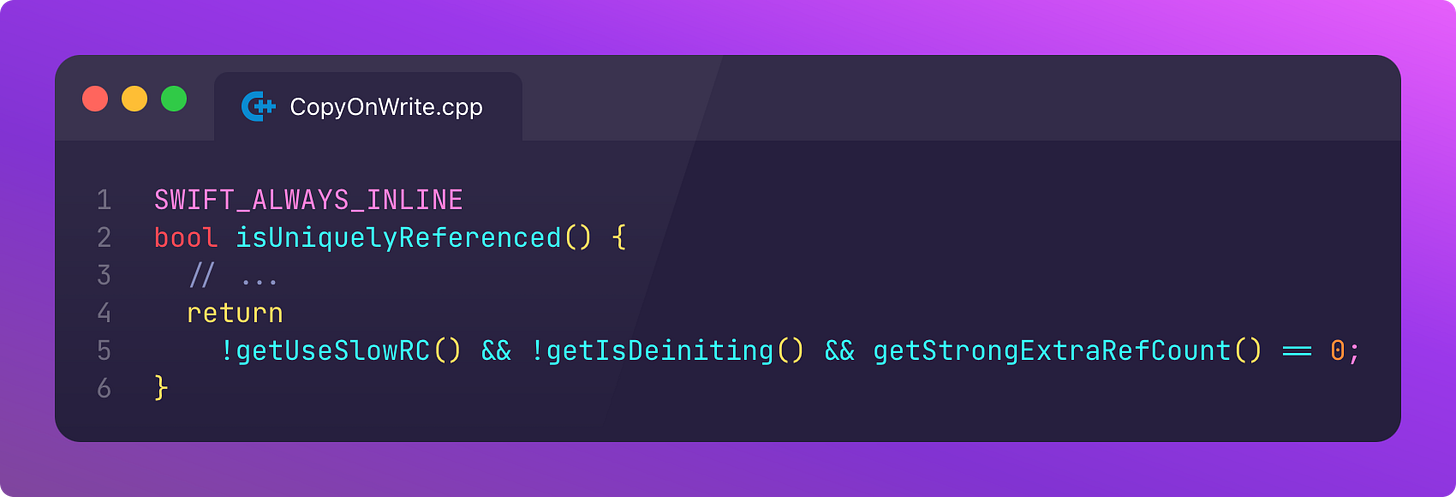

Next, we can see the underlying implementation of isUniquelyReferenced():

getUseSlowRC checks whether there’s a side table storing overflowed pointer counts; and getIsDeiniting is fairly self-explanatory: deinitialisation only happens when a strong reference count is already zero.

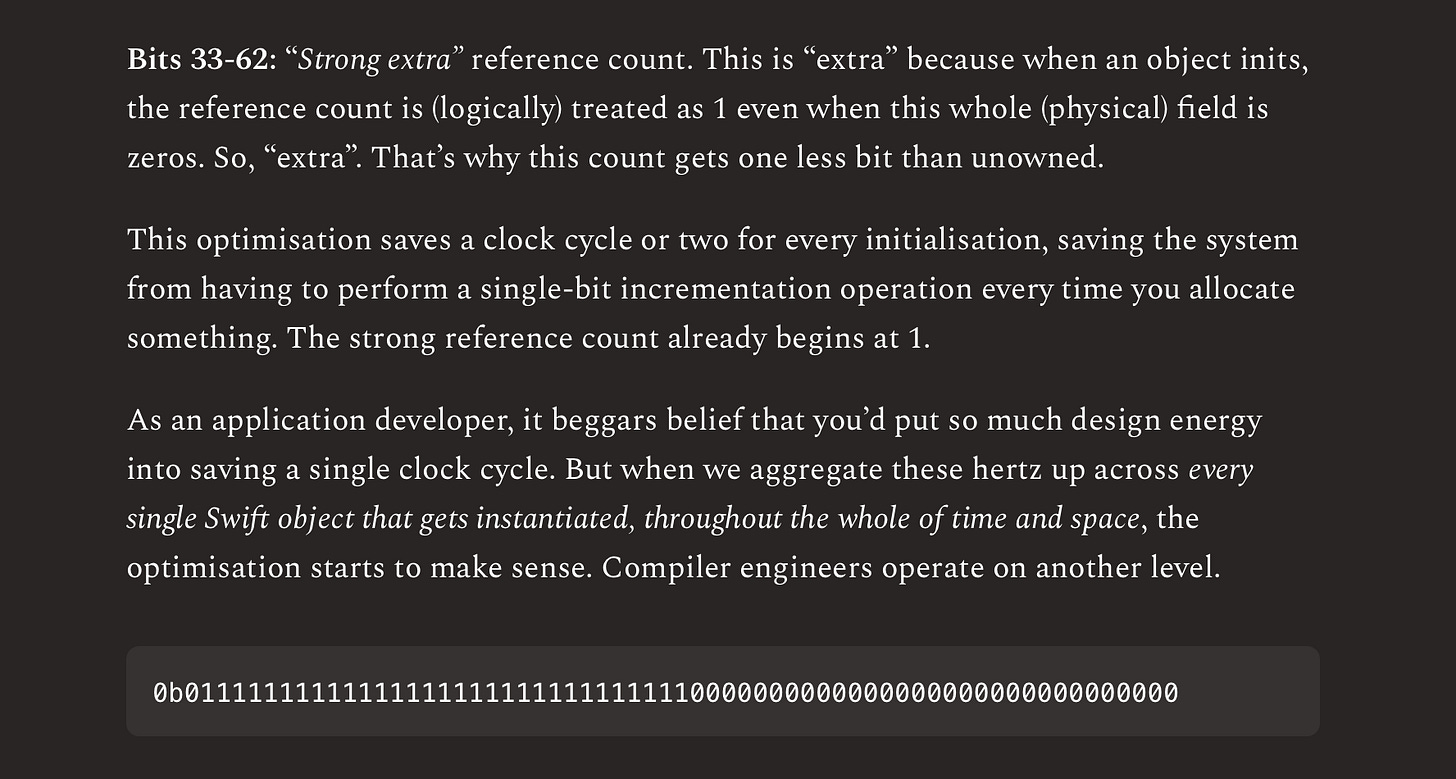

The most important part here is getStrongExtraRefCount() == 0. Scrolling up to the documentation inline, we find:

The strong RC is stored as an extra count: when the physical field is 0 the logical value is 1.

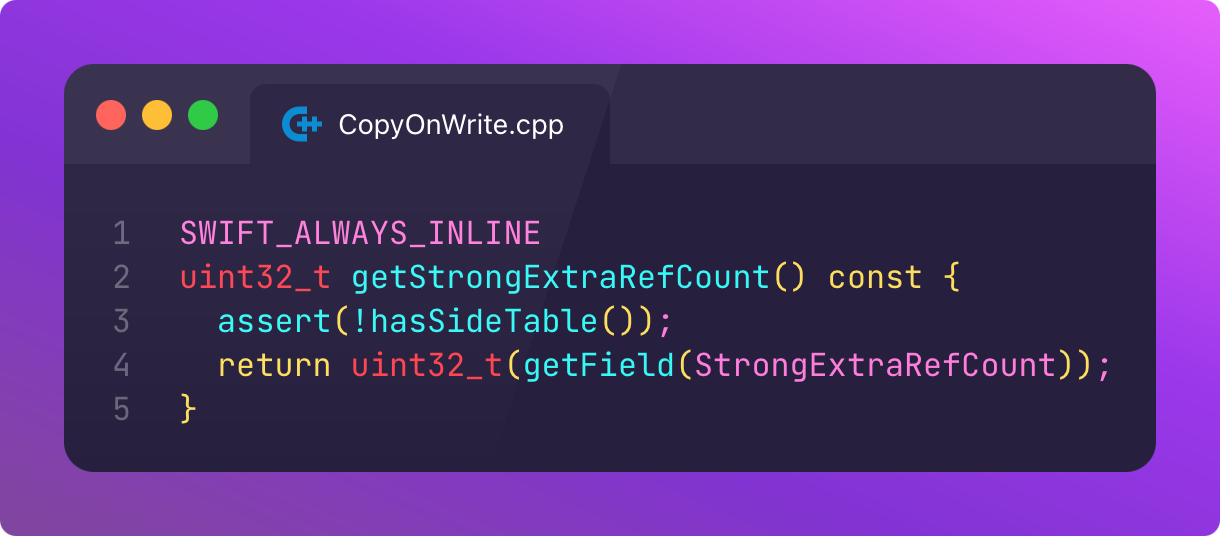

If an object has exactly one strong reference (logical), the bits representing the strong reference count are 00000000 (physical). The getStrongExtraRefCount function finds us the strong reference count that we’re looking for, StrongExtraRefCount:

Here, we call into a C++ macro that returns the StrongExtraRefCount field stored in RefCount:

These macros operate directly on the bits stored by RefCount to return the integer value of StrongExtraRefCount. These bitwise operations can be dense, so let’s take this step-by-step:

The logical number StrongExtraRefCount is stored in the bits in RefCount‘s memory layout, bit-packed with other metadata (unowned count and flags) to save space.

Let’s say the memory layout for the RefCount looks like 00101010 (in reality, it’s 64 bits wide, I’ll actually show you in a minute).

The bit-mask has 1s for the locations of the bits that represent the StrongExtraRefCount, e.g., 00001100.

We can run a bitwise & operation to isolate just those bits, 0-ing out the rest of the data: leaving us with 00001000.

The offset ##Shift contains the number of “significant” digits which the StrongExtraRefCount lives at, which in this example is two bits from the end (in this one-byte example, we don’t need to fret about endian-ness).

The right bit-shift operator >> shifts our bit-masked data to the right, returning 00000010.

This, in full binary glory, is the strong extra reference count we’re looking for: 10, or “2” if you’re a decimal normie.

Therefore, our object has three strong references, meaning it’s not uniquely referenced!

I’ll encourage you to read “Bits and Side Tables” once again because I show you the actual physical bits inside RefCount:

The isKnownUniquelyReferenced Meme

We’ve finally determined how isKnownUniquelyReferenced is working behind the scenes to power our 🐮 optimisations.

It’s all a bit obvious, really.

Each time a new pointer is created to reference an object stored on heap memory strongly, it increments the strong reference count of that object.

isKnownUniquelyReferenced simply slips through its backchannel into the runtime to ask whether the object’s strong reference count is equal to 1.

(Accessible version of the meme)

isKnownUniquelyReferenced just checks the strong reference count = 1

isUnique in the Swift Standard Library calls a Builtin function

The Abstract Syntax Tree synthesises Builtin functions so they can be called like regular Swift functions

Swift Intermediary Language emits the IsUniqueInst instruction, which performs the uniqueness check

The LLVM IR instruction generates the emitIsUnique instruction, which calls into the Swift Runtime ABI

The Swift Runtime inspects the bits on a HeapObject which stores the strong reference count

isKnownUniquelyReferenced just checks the strong reference count = 1

Last Orders

When I first casually looked into isKnownUniquelyReferenced back in 2023, I had no idea what I was getting into. I assumed I’d poke around the Swift Standard Library, find some funny private API that tracked a sneaky reference count property somewhere, and call it a day.

Curiosity is a heavy burden.

Like Dante, I kept pressing forward.

Into the haunted woods of the Standard Library source code. Through the purgatorial hallways of Builtin definitions. Deeper and deeper, through the infernal circles of the Swift Compiler: the Abstract Syntax Tree, Swift Intermediary Language, and LLVM IR. Until finally, paradise was found in the Swift Runtime and SwiftShims.

Today, Swift Internals is a core pillar of Jacob’s Tech Tavern.

I hope you had fun, learned a lot, and, most importantly, I hope you get the chance to flex your unbeatable 🐮 knowledge the next time you get an iOS job interview.

If you liked my post, subscribe free to join 100,000 senior Swift devs learning advanced concurrency, SwiftUI, and iOS performance for 10 minutes a week.

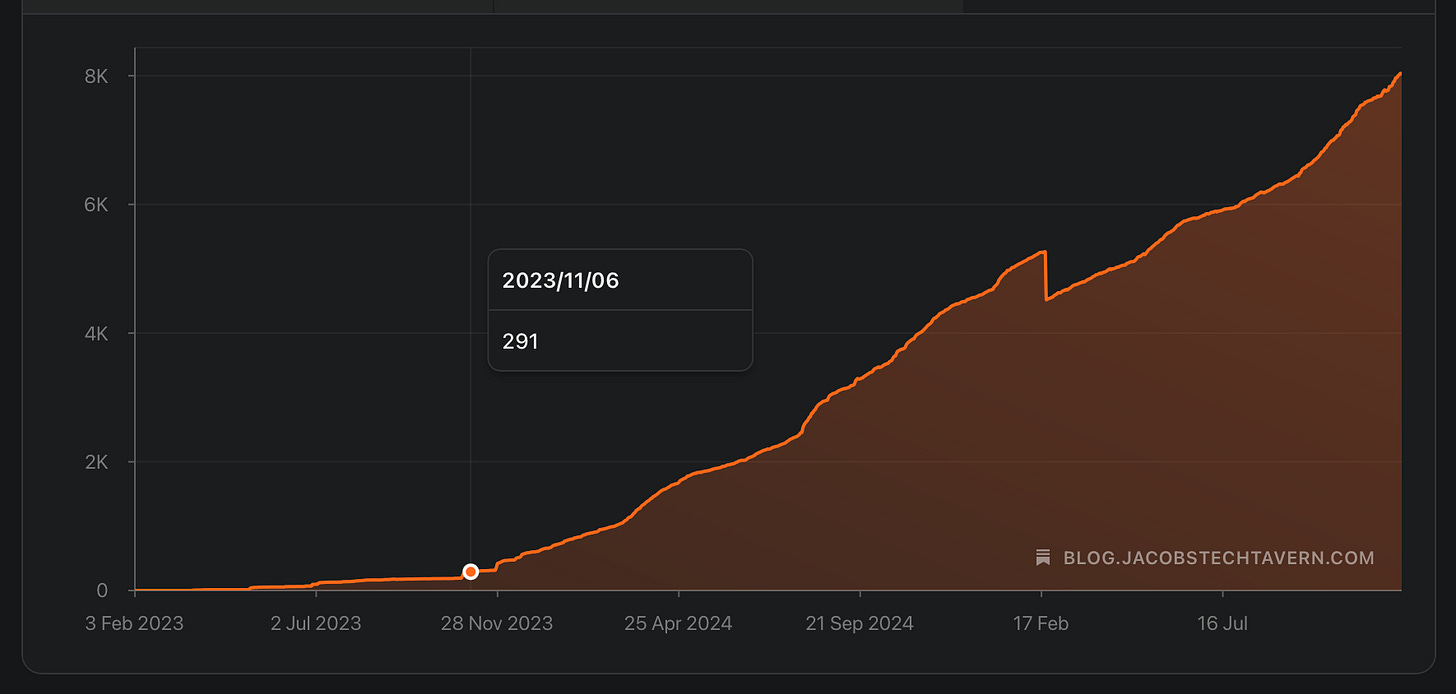

This is a full re-write my most underrated post of all time. Nobody read it, because I only had 291 subscribers at the time. Really.

I hope I can bring the joy to a new generation of subscribers.

COW2LLVM: The isKnownUniquelyReferenced Deep-Dive

·Subscribe to Jacob’s Tech Tavern for free to get ludicrously in-depth articles on iOS, Swift, tech, & indie projects in your inbox every two weeks.

And if you liked this post, you will love this:

How to Learn the Swift Source Code

·Today I’m selling shovels. A treasure map. The equipment you need to tunnel through the Swift source code and mine out the nuggets of arcane knowledge reserved for C++ and compiler geeks.

I love this content. Reminds me of the *OS Internals books by Jonathan Levin, but if he wrote them while slightly intoxicated at the pub.