Method Dispatch in Swift: The Complete Guide

How does Swift *really* execute function calls?

If you’re like me, you’ve worked with a grizzled staff engineer that generously doles out helpful nitpicks to improve the performance of your code.

Perhaps, like me, you’ve also been that grizzled engineer.

You know the sort.

Nitpicks like “this method should be declared fileprivate”, or “keep your generics in the same file where they’re used”, and the all-time classic “mark this function as final” to help out the compiler and speed up your code.

In modern Swift, you might as well spend your time writing branch prediction hints for the compiler. That is, the compiler and runtime do a ton of optimisation under the hood that makes these tips redundant.

These optimisations are mostly around Method Dispatch.

That is, how Swift executes function calls. This knowledge is crucial for understanding the low-level performance characteristics of your code.

Today we’re going to learn:

How (and why) Swift implements all 4 types of dispatch

What the Swift compiler does to your methods in secret

How the Swift runtime calls into your functions at runtime

How to make your code run faster

How to build an intuition about method dispatch

Subscribe free to join 100,000 senior Swift devs learning advanced concurrency, SwiftUI, and iOS performance for 10 minutes a week.

Method Dispatch

In broad Computer Science terms, “method dispatch” is the process for telling the CPU where to find executable code in memory for a function call.

Method dispatch can be static or dynamic, but these break down into 4 sub-types. As you move down, method dispatch becomes more flexible, but slower: The types create a bidirectional hierarchy of speed & flexibility.

This hierarchy is defined by indirection. That is, the number of times the CPU has to jump between pointers to find the machine code for a function.

Inlining (fastest, not flexible)

This optimisation unrolls a method’s contents directly onto the code path.Static dispatch (fast, not flexible)

The function’s memory address is known, so the CPU jumps straight to it.Table dispatch (slow, flexible)

The CPU jumps twice: once to a table of pointers (to potential implementations), then once to the correct implementation.Message dispatch (slowest, very flexible)

There might be multiple jumps as the runtime traverses class and superclass metadata to locate method implementations. This dynamic approach implements caching that can speed it up past table dispatch once it’s ‘warmed up’.

Most languages pick just one or two approaches:

C only uses static dispatch since it is designed around predictable low-level performance.

Java only implements table dispatch because of its focus on portability, meaning the JVM must always be able to load classes dynamically.

Objective-C uses message dispatch because it is deliberately built for runtime dynamism, with language features like swizzling and method forwarding.

Swift implements all 4.

This is due to the scope of the language.

Swift is (designed to be) as performant as C when using value types like structs and enums, which use static dispatch.

Swift also supports classes, protocols and generics, which rely on the more flexible table dispatch to locate relevant implementations.

Message dispatch, honestly, is a legacy Objective-C holdover. Swift had to be fully compatible with Obj-C and UIKit in order to achieve adoption from the aforementioned grizzled staff engineers.

This is a double-edged sword: Swift gives engineers fine-grained control over the performance characteristics of their code; but this scope also introduces many of the gotchas and misunderstandings that trip up less experienced Swifties*

(I’m pretty sure this is what they call us).

Inlining

This is the fastest approach, and is actually not dispatch at all. Inlining is a compiler optimisation which replaces the call to a function with the actual code from inside that function.

We don’t usually control this*. The Swift compiler makes the call about inlining function calls during its SIL optimisation stages.

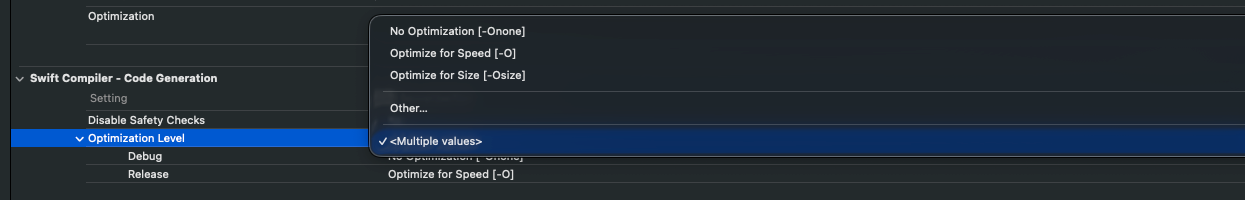

*but you can influence it by selecting size vs speed compiler optimisations.

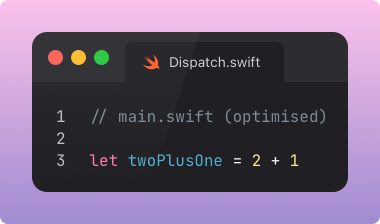

Let’s say you had the following code:

If the compiler decides to inline this, the compiled Swift might be equivalent to this:

Here, the call to the addOne function is just replaced with the operation num + 1, where num is replaced with our argument, 2.

Pre-computing

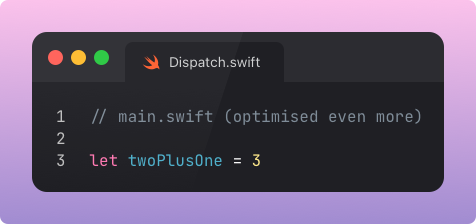

The compiler can go further.

Since these numbers are hardcoded, the compiler actually has all the information it needs to calculate this result at compile-time. It can, literally, pre-compute the result we need here, giving us a simple number.

Inlining skips dispatch entirely, but pre-computing avoids runtime execution altogether. No work needs to happen in our (hopefully) millions of users’ devices at runtime.

Swift Intermediate Language

Before compiling your code down to machine language, the Swift compiler converts it into Swift Intermediate Language (SIL), where it runs through many optimisation passes.

You can generate SIL yourself from Swift code like this:

swiftc -emit-sil -O main.swift > sil.txt

-O tells the compiler to run optimisations for speed, which include inlining. -Osize in contrast optimises for smaller binary size, making the compiler less likely to inline. Copying a function into multiple places inline can grow binary size.

Learn more about SIL in my mini-deep-dive:

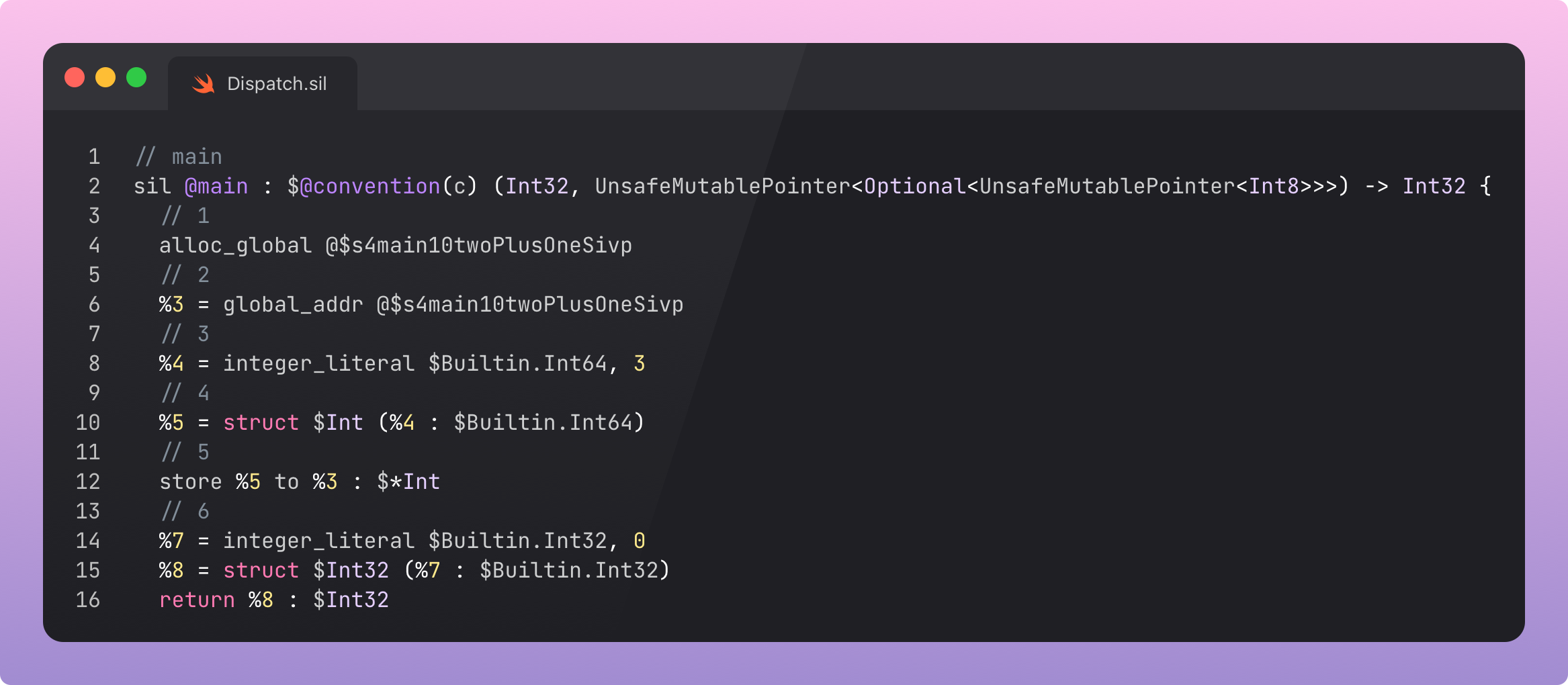

The resulting arcane hieroglyphs allow us to see the optimisations in person:

I omitted most of the code for brevity (4 lines of Swift turns into 78 lines of SIL!), but we can see inlining in action:

Memory is allocated for the twoPlusOne property.

The pointer address of our twoPlusOne property is assigned.

An integer literal for 3 is precomputed and inlined.

This value converted into an Int struct from the Standard Library.

This Int is stored at %3, the memory address of twoPlusOne.

You’ll usually see these lines at the end of a main() function. This is simply exiting the program with code 0 (i.e. without an error).

SwiftRocks has a great article if you want more of a deep-dive on inlining and the undocumented @inline attribute.

Why is inlining so fast?

While SIL does not map 1:1 onto ARM assembly instructions (you need to run swift -c for that!), it is pretty intuitive that less SIL will execute faster than more SIL.

To truly peer behind the veil, we need to touch the metal: what is happening on the CPU when you call a function?

There is Overhead each time you invoke a function. The CPU caches the data on its registers, jumps the instruction pointer to a new memory address, and restores state after function execution.

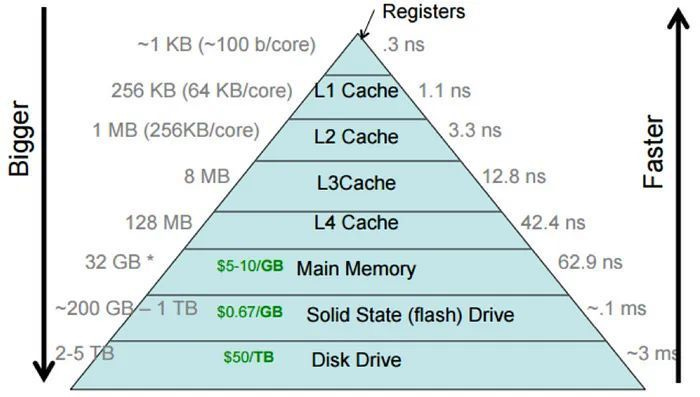

An executing binary lives primarily in a chunky TEXT file stored in memory. Segments of executing code are copied to the CPU Caches, which are accessed 100x faster than RAM. A slow cache miss happens if a function has to be loaded from memory.

CPUs utilise Pipelining to handle multiple instructions simultaneously. When it needs to wait for a new function to be loaded in from RAM, the instruction pipeline may be disrupted, stalled, or even invalidated entirely.

The CPU applies Branch Prediction to estimate which code paths are likely to run next, allowing it to fill the pipeline with the most likely paths (and even look ahead with predictive execution). Jumps to function calls can easily disrupt a CPU’s ability to predict outcomes.

Learn more about binaries and TEXT here:

I’ve also written a lot about registers, CPU caches, and pipelining here:

Due to all these factors, inlining and pre-computation are powerful tools in the Swift Compiler’s arsenal for optimising your code for pure speed.

Static Dispatch

This is also known as direct dispatch or, occasionally, compile-time dispatch. These names all describe what’s going on:

static implies that the location of the function in memory is fixed…

…and knowable at compile-time.

Therefore, only one jump is required to find and execute the function, directly to the memory address of the function in the binary.

static functions in Swift, as well as functions on enums and structs, use static dispatch. The compiled machine code of these functions is stored at a known address in memory when a Swift program launches.

This deterministic nature of static dispatch enables the compiler to easily run optimisations such as inlining and pre-computation.

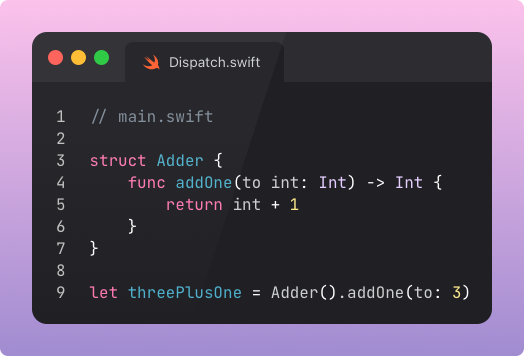

Let’s see this in action with a very basic struct, with another addOne function:

Let’s generate the Swift Intermediate Language for this code and see what’s going on under the hood of the compiler.

Again, I’ll massively cut down the 97 lines of generated SIL for this 7-line

main.swiftfile to avoid information overload.

Let’s see what became of our main function:

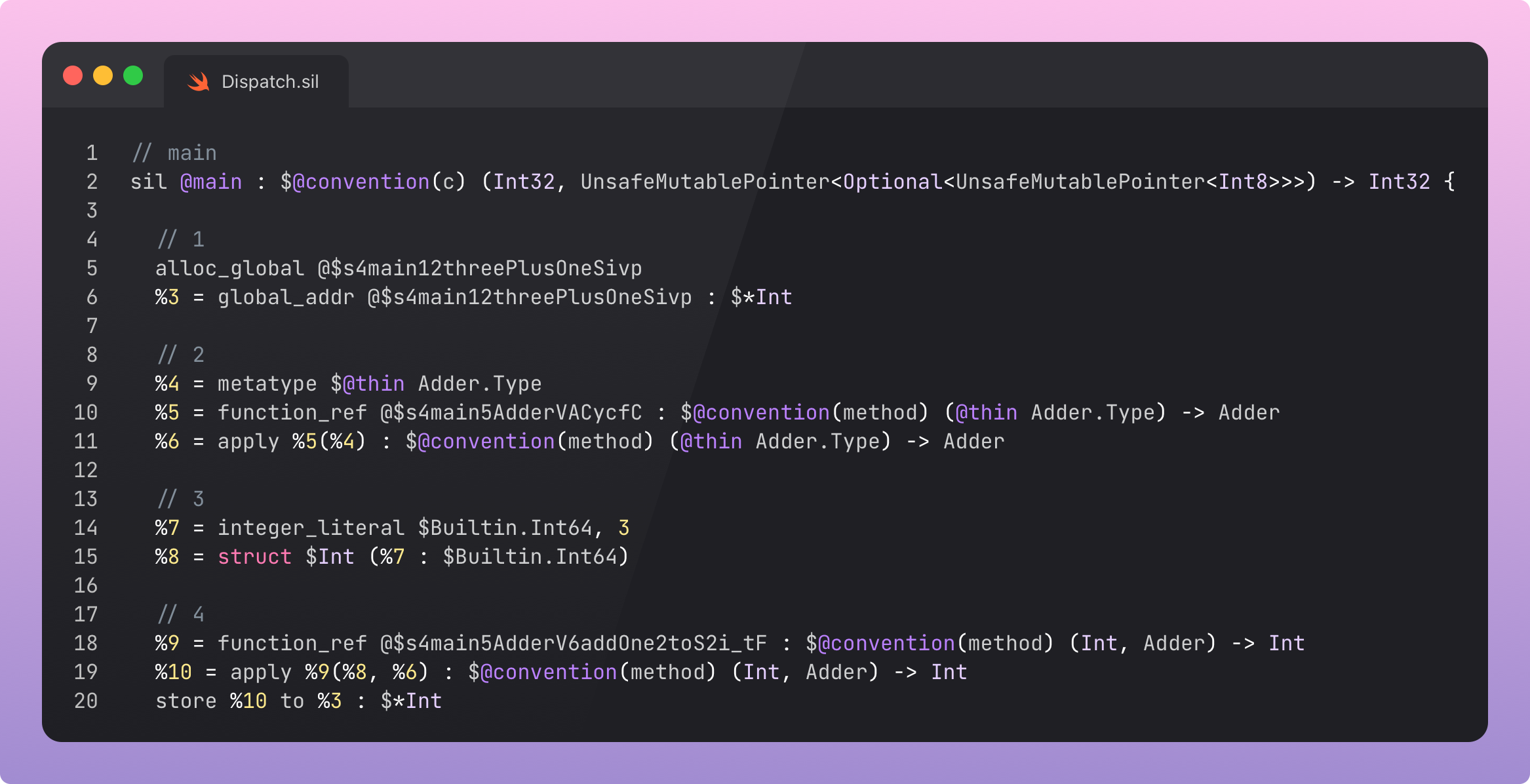

Memory is allocated for the threePlusOne property.

The function call for the Adder struct’s init function is called.

You thought struct initialisers were implicit? They are, until the compiler generates it!

apply is the SIL instruction for calling a function, taking %4 (the type) as an argument for %5 (the function).Next, the integer literal for our function argument , that is, the number 3, is instantiated. First a Builtin Literal is called, then an Int is initialised.

Finally, our addOne function is called; creating a function pointer function_ref, and passing the arguments created before: the Int and the Adder.

The calling convention of SIL looks a lot like Python: self, the instance, is explicitly passed to the call site of its methods.

This is because the methods on a type are shared between all instances in memory. Therefore, a reference to the instance is required to access or mutate any properties.

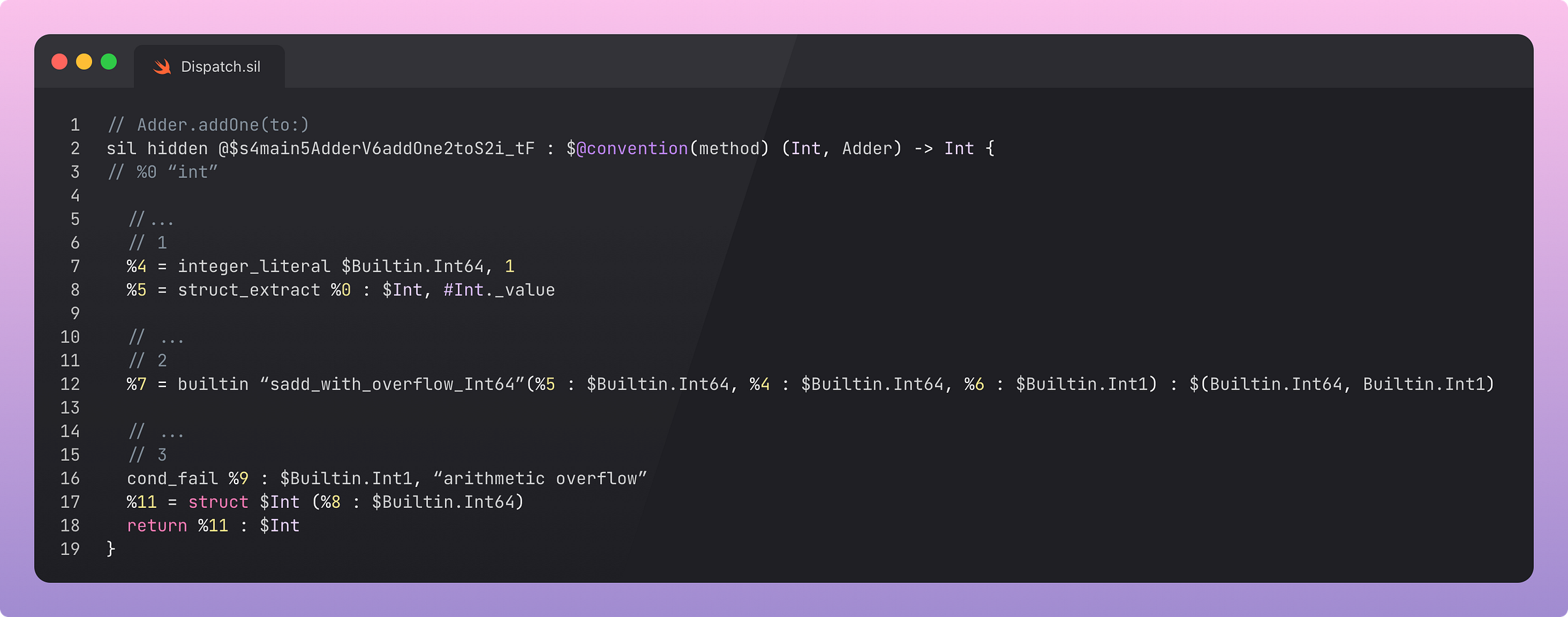

The definition for our addOne function is found here as well:

An integer_literal is declared using 1, and the integer value of the input argument is extracted.

This is where the magic happens: the actual functionality of the Int.+ function is inlined here using the Builtin implementation.

There is some nifty error-handling that detects arithmetic overflow (i.e. values over 2⁶³-1); and the result Int is instantiated and returned.

I won’t go into more detail here, but the Int.init(_builtinIntegerLiteral:) initialiser and the Int.+ infix(_:_:) functions are also both defined in SIL.

Not sure what is meant by Builtin? Read this post if you want to become absolutely sick of seeing them.

When compiling this SIL with optimisations, the addOne function itself is inlined straight to the call site; and the Int.init() and Int.+ functions disappear entirely.

The Swift compiler collapses entire chains of statically-dispatched function calls inline to extinguish many expensive function calls at once. Such is the power of direct dispatch.

Dynamic Dispatch

This is also known as table dispatch, or sometimes runtime dispatch (some of these words are straightforward) . Basically, the function we dispatch to is dynamically chosen. This means chosen at runtime.

Table dispatch isn’t as obvious semantically, but divulges an implementation detail: a table of pointers. This table is critical for implementing polymorphism. The power for a single type to have multiple formes.

Before you shout at me, yes, Swift actually implements two flavours of table dispatch: virtual tables for class hierarchies, and witness tables for protocols.

Virtual Table Dispatch

Consider a very basic class hierarchy involving the Felidae family (to use the most precise taxonomical term, look it up).

Here, the subclassing relationship implies that a Lion is “a kind of cat”. If this code was part of an open-source Animals package (and marked open, so subclassable in other modules), we could import it and subclass Cat ourselves, with a custom implementation of cry().

Therefore, if you use a Cat subclass in your codebase, it might roar, since Lion is a possible subclass of Cat. Swift also needs to handle other possible implementations of cry() for any other subclass of feline*.

Since our .swift files are compiled independently**, the Swift compiler can’t be sure which implementation is going to be used where. This information is only available at runtime . Until the object is actually created, we don’t know whether we’re dealing with a bog-standard kitty or the king of the jungle***.

*Let me be clear, I mean “class” Swift-onomically. Taxonomically, cats and lions are a Family, and they’re both from the class “Mammal”. A superclass if you will. Sh*t.

**.swift files compile independently when whole-module optimisation is not active. I’ll go into more detail in Making Your Code Go Faster in a moment.

***Shouldn’t it be “king of the savannah”?

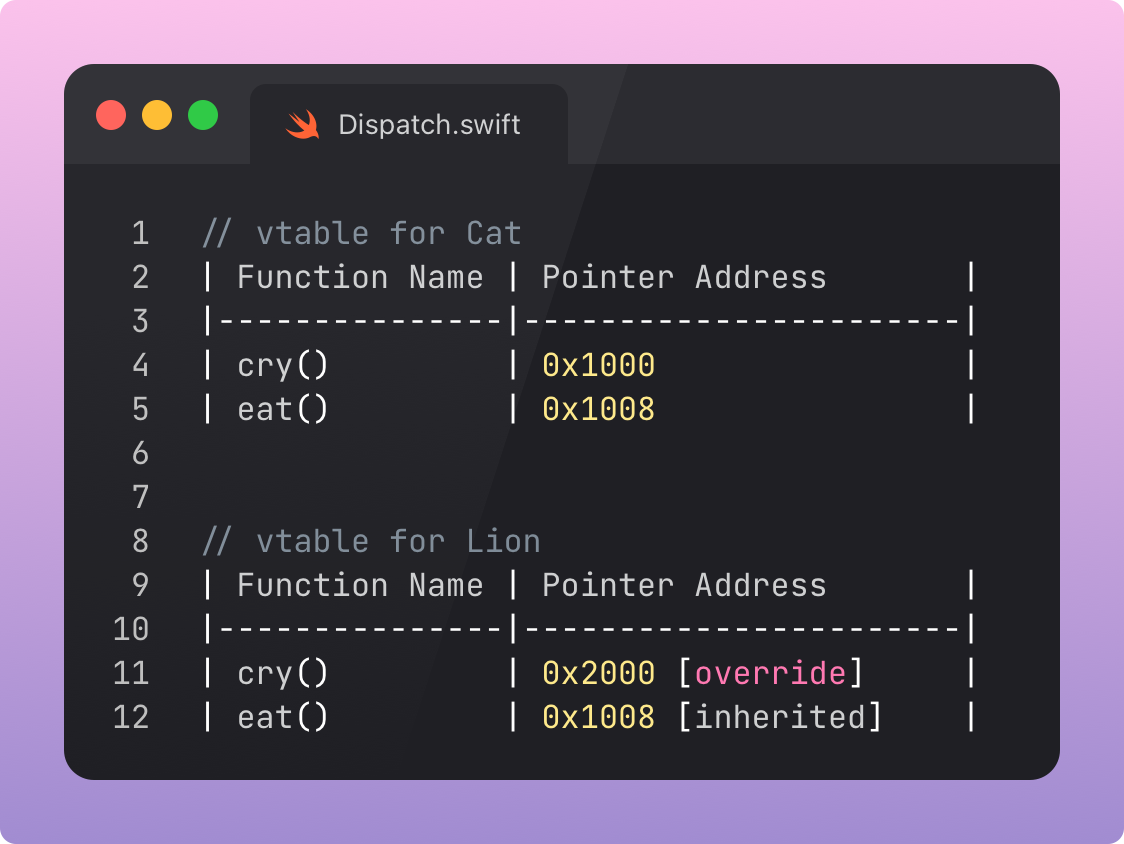

The virtual table isn’t magic at all.

It’s a list, built at compile-time for each subclass, mapping each function to its implementation in memory.

If Lion overrides cry(), then the table points at the instructions defined on Lion.cry().

If it doesn’t override eat(), then the virtual table for Lion will point at the instructions defined in the Cat superclass.

This is the indirection I was talking about before.

Table dispatch is slower than direct dispatch because at runtime, to dynamically dispatch to a function, the runtime first needs to:

Jump the instruction pointer to the virtual table stored in the subclass type metadata in the binary.

Pick out the correct function pointer from this table.

Jump the instruction pointer, again, to the function’s memory address elsewhere in the binary.

Cool. What about the other tables?

Protocol Witness Tables

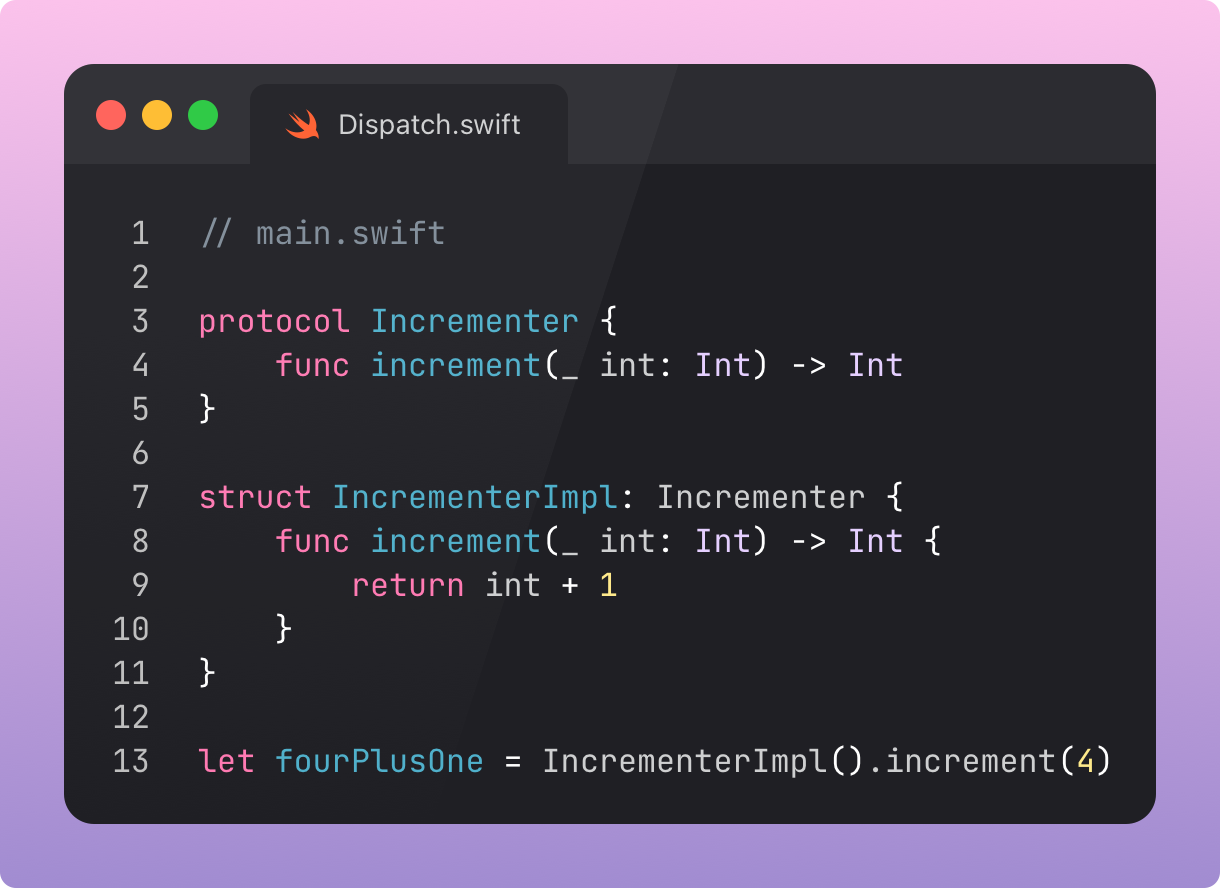

Protocols allow developers to add polymorphism to types through composition, even to value types like structs or enums. Protocol methods are dispatched via Protocol Witness Tables.

The mechanism for these is the same as virtual tables: Protocol-conforming types contain metadata (stored in an existential container*), which includes a pointer to their witness table, which is itself a table of function pointers.

*Existential containers are an underlying implementation detail of protocols. To understand these in more detail, check out the in-depth essential WWDC talk, Understanding Swift Performance (2016).

When executing a function on a protocol type, Swift inspects the existential container, looks up the witness table, then dispatches to the memory address of the function to execute.

It’s not necessarily all indirection and jumps though.

The witness table dispatch happens if the type you’re dispatching to is an abstract protocol type. If you specify the concrete type of something conforming to the protocol, then the specific implementation of the code is known at compile-time, and can be dispatched statically.

(I’ll go into this in more detail in Building Up An Intuition soon)

Then why use abstract types?

Anything mockable, for instance. We often use abstract protocol declarations when performing dependency injection: we specify the protocol ; the interface our dependency conforms to ; without a concrete type, injecting an implementation at runtime.

Other times, we might have a Collection containing various protocol-conforming objects we want to iterate over. In these cases, method dispatch is via the witness table.

The term “witness table” is borrowed from constructive logic, where proofs serve as witnesses for propositions. In my opinion, though, this kinda-sorta feels like a post-hoc justification . They already used the term “virtual tables” for dynamic dispatch with subclasses. I reckon our boy Lattner just needed a different phrase to distinguish the concept.

Table Dispatch in Swift Intermediate Language

As mentioned, there are two main ways to invoke dynamic dispatch in Swift.

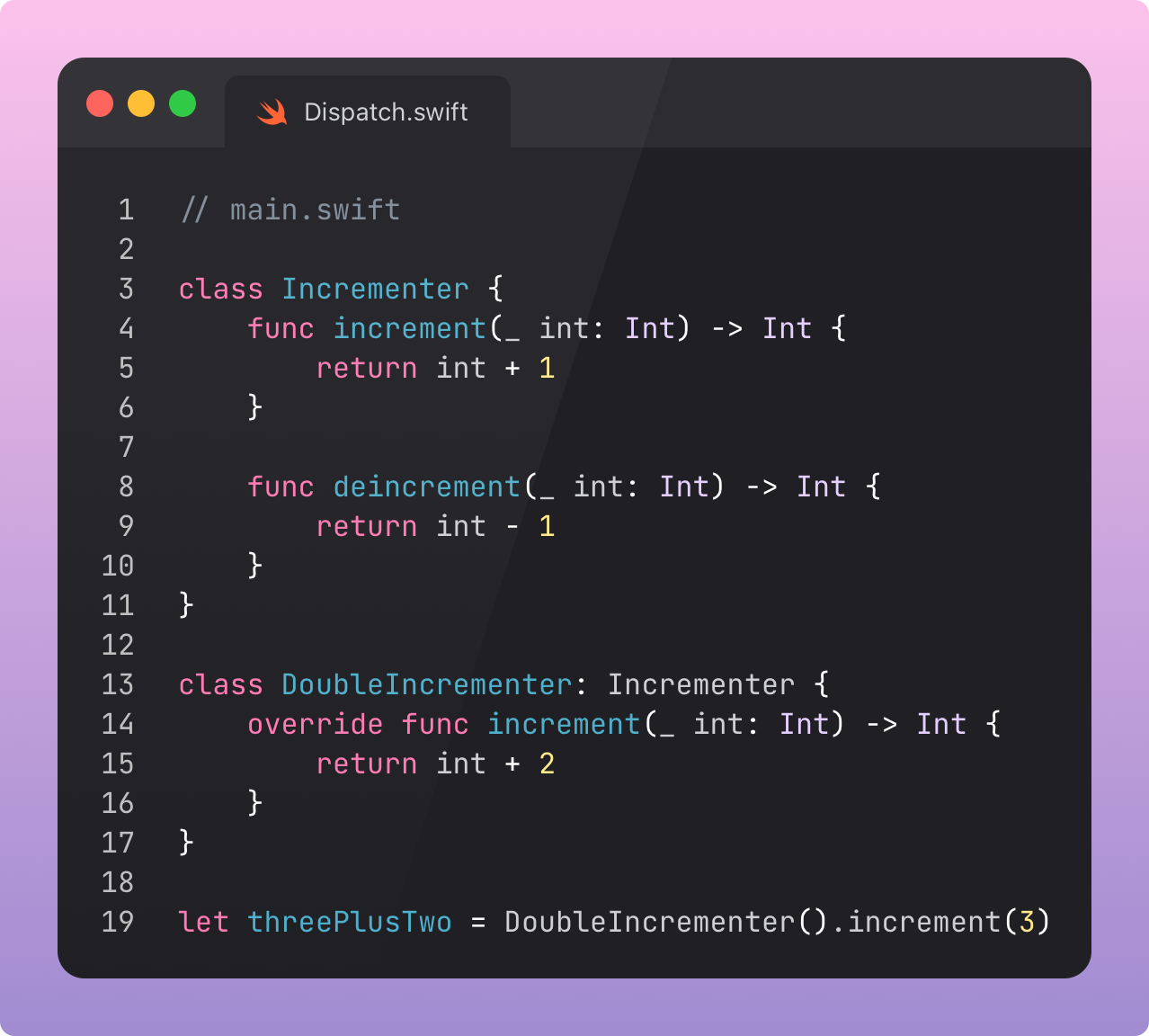

First, let’s look at the vanilla virtual-table dispatch you might find in a language like Java or C++.

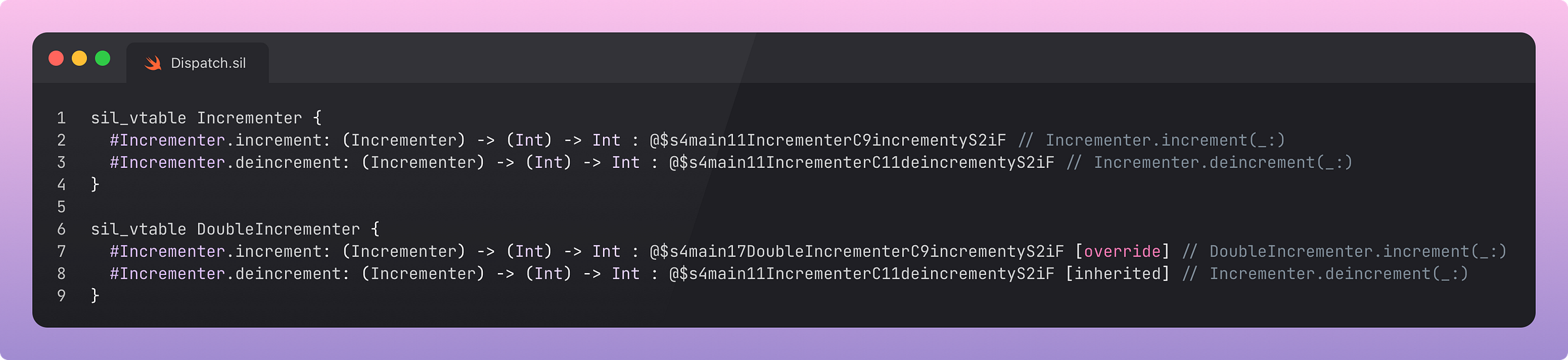

We can see the virtual tables (a.k.a. vtables, if you’re a cool kid) created in the SIL. DoubleIncrementer implements both methods, but only overrides one with a pointer to its own implementation:

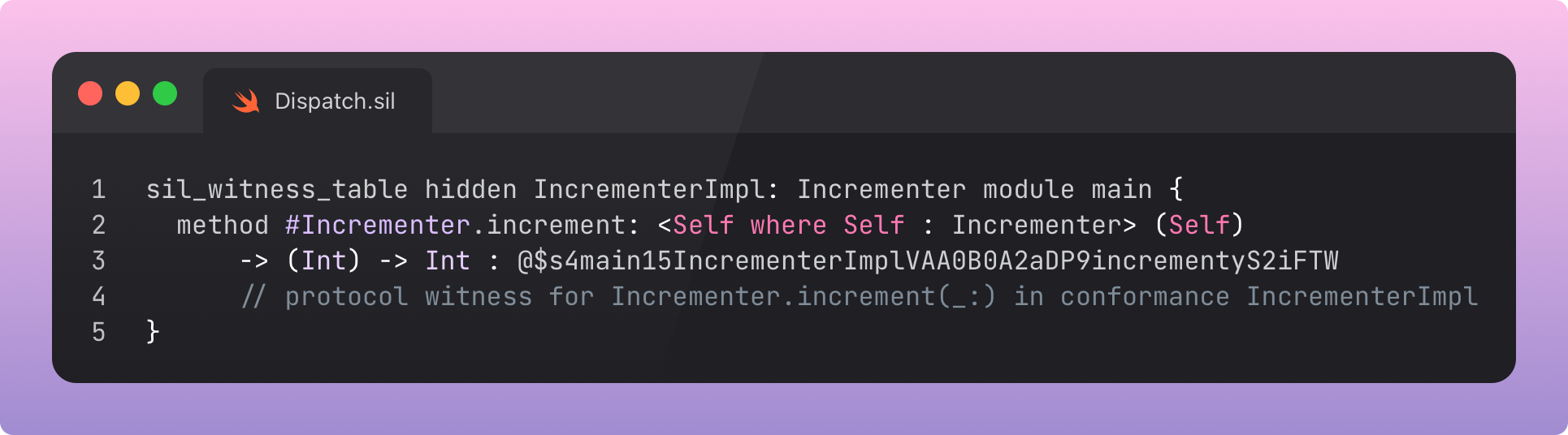

Let’s see how it looks when we use a protocol:

This time, we see a witness table (sil_witness_table) in the SIL we generate:

In both of these very simple examples, the compiler actually ends up statically dispatching the main() function straight to the method implementation of increment(), bypassing the dispatch tables. Agh!

If you compile with optimisations, Swift drops the functions entirely and produces precomputed results at the call site. Dammit!

The compiler won’t give you what you want; it’ll give you what it thinks you need…

Message Dispatch

Message dispatch is the most dynamic tool in Swift’s repertoire of dispatch approaches. It’s so dynamic, the implementation of a method can be changed at runtime through swizzling. It’s so dynamic, it doesn’t actually even use Swift . It lives in the Objective-C runtime library. Huh?

Message-dispatched function invocations are dispatched using the ObjC runtime’s objc_msgSend function. Instances of Objective-C classes have an isa pointer which points to the “class object” , the implementation of the type in memory.

What’s an isa pointer? Boy do I have an article for you!

objc_msgSend follows isa to the class, then inspects its table of method selectors. If the method is found, it’s executed. If not, then the runtime follows the super pointer to the superclass table. If the method is still is not found, the runtime iterates through the object hierarchy, until the method is found or it hits NSObject, the ObjC root object.

This table of method selectors is implemented as a message passing dictionary, which is mutable at runtime. This is how ObjC implements its famous method swizzling.

The ObjC runtime caches memory addresses of methods as they’re used. Calling a cached method is about as fast as a regular table-dispatched function call, making message dispatch quite quick once the program has run for a while and “warmed up” the cache.

Look.

If you want my honest opinion, nobody implementing a language today would have even considered message dispatch . It’s a legacy holdover from the fact that virtually all of Apple’s frameworks have been implemented in Objective-C since time immemorial, including Core Data, UIKit, and Swift’s KVO.

It’s pretty neat though.

Message Dispatch in SIL

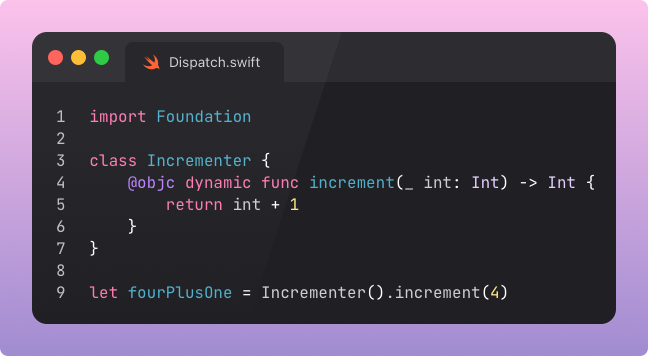

To invoke message dispatch in Swift, you need two things:

The @objc attribute, which tells the compiler to make a class, property, or method available to the Objective-C runtime.

The dynamic keyword, which tells the compiler to invoke the property or method via message dispatch.

Let’s write our final main.swift:

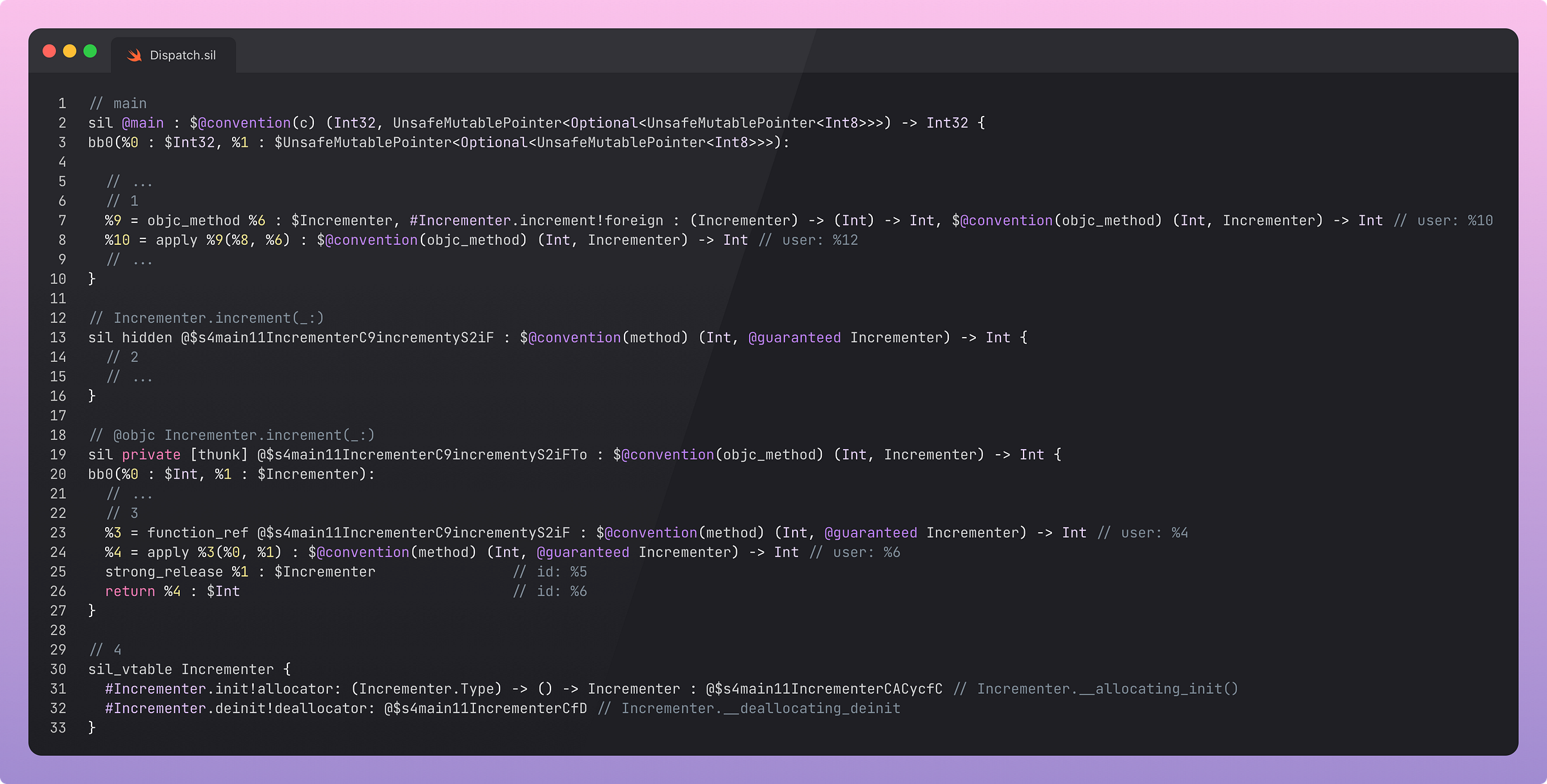

And now let’s take a look at the SIL output:

Here, the objc_method on Incrementer is invoked in our main() function.

Note the #Incrementer.increment!foreign to denote that the method is using something outside of native Swift.When you have an @objc method implemented with Swift, both a Swift flavour and an Objective-C flavour of the method are emitted in SIL.

This redacted SIL code is identical to the statically-dispatched logic we looked at earlier (since we will call into it!).Here, in the @objc Incrementer.increment(_:), [thunk] lets the Objective-C runtime statically dispatch to the Swift implementation of the method.

Using a separate ObjC function like this allows Swift-native code to call straight into the Swift version straight away (and eschew slower message dispatch).Methods marked dynamic do not appear in the v_table, since regular table dispatch is not used to resolve the method call.

Message Dispatch. Huh. Yeah. What is it good for?

Message dispatch is certainly not the hammer you want to smash into every programming nail, but it shines in the right use case. Take Realm for example ( yes, I know it’s called Atlas Device SDKs now, but that’s also the lamest rebrand I’ve heard in my life)*.

*Atlas Device SDKs, please sponsor my Substack.

Using Realm on iOS, you need to mark the properties on your database objects @objc dynamic. This is to expose them to the Objective-C runtime. This enables message dispatch on the model properties, and hence powers key-value observation!

Under the hood, this KVO uses method swizzling to replace the getter and setter of a property with customised read/write methods. This in turn allows database objects to dynamically update whenever the underlying data is modified.

Making Your Code Go Faster

This is all really nice theory. The whole article. Wow. Well done, Jacob.

But outside of impressing your wife with your stonking depth of comp-sci knowledge, theory isn’t useful unless you can apply it.

Let’s discuss how your knowledge of method dispatch can help your own code run faster and more efficiently.

Reducing Dynamic Dispatch

The compiler works hard to optimise your Swift code before anything runs.

From the Swift repo’s own explainer on SIL:

If the static type of the class instance is known, or the method is known to be final, then the instruction is a candidate for devirtualization optimization. A devirtualization pass can consult the module’s VTables

to find the SIL function that implements the method and promote the instruction to a static function_ref.

Outside the specific context of trying to demonstrate bloody dispatch methods for a blog post*, this is optimisation is generally considered pretty useful. There are several things we can do as developers to help the compiler out, and speed up our Swift code.

*I had to muck around with

swiftc -emit-silfor a while to stop the compiler optimising away all my dynamic method calls in the SIL sample code.

Since I am now one with the Swift compiler; I was unable to resist inlining this information here instead of just linking you to the docs.

final and private keywords allow the compiler to optimise a class or method to use static dispatch, because it can infer there is no dynamic polymorphism on those methods. But this tip is largely redundant now that Whole Module Optimisation is on by default. The compiler processes a module’s files all together (rather than each .swift file individually, meaning internal classes and methods can be inferred as final.

Cross-module optimisation takes things a step further and enables optimisations like devirtualisation (dynamic to static) and inlining (static to inline) across module boundaries, even for public functions.

This is set at a conservative level by default, because these optimisations improve speed but can impact code size.

You can explicitly opt into more aggressive optimisations, using compiler flags in your module’s Package.swift:

// Package.swift

targets: [

.target(

name: "MyAwesomeModule",

swiftSettings: [

.unsafeFlags(["-cross-module-optimization"], .when(configuration: .release))

]

)

]You can opt out using -disable-cmo.

Performance Characteristics

The actual performance impact of the dynamic dispatch is, usually, fairly small : the additional layer of function call indirection is only a few extra CPU instructions, or clock cycles.

There are, however, two big ways in which dynamic dispatch has an impact on runtime performance:

The compiler loses the ability to perform optimisations like inlining or precomputing.

Indirection can increase the likelihood of a cache miss. Since the location of a function isn’t known at runtime, instead of the CPU reading its instructions from the L1 cache (1ns), your program may need to fetch the function code from RAM (100ns).

Why can’t we just work out all the concrete types at compile-time?

I’m glad you asked.

The whole point of polymorphism is that concrete types aren’t fully known at compile-time, so runtime behaviour can vary. This allows us to write flexible code, where implementations aren’t instantly known the minute you type out your protocol.

But when we are bounded within a region of known access control, we can know the implementations at compile-time.

Consider the guidance the Swift team gives us about reducing dynamic dispatch . final, private, and whole-module (or cross-module) optimisation.

This gives the compiler more information.

Therefore the compiler can work out whether a type is knowable at compile-time, and therefore whether it can be converted to static dispatch and all its consequent optimisations.

Building up an intuition

Due to its support of all the dispatch methods, Swift has many unintuitive gotchas about how certain types of method are dispatched.

When you understand the underlying mechanisms of static and dynamic dispatch , and the information available to the compiler, we can actually work out how these quirks come about.

The canonical example

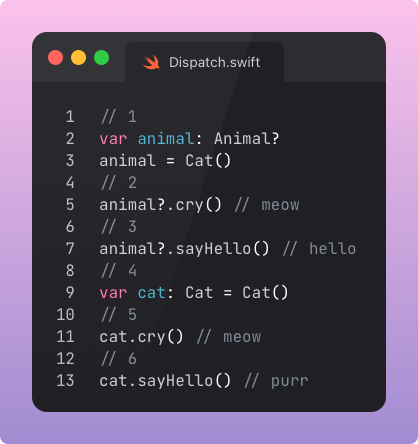

Protocols are commonly invoked to demonstrate this “odd quirk” (but not really) to your interns. With protocols, you can impact dispatch behaviour via the type declaration .

See this example with a protocol, an implementation, and default methods on the protocol extension:

When you call into these functions, the type declaration you use when instantiating your class affects whether you get static or dynamic dispatch.

Feel free to copy this code into a Swift playground and see for yourself!

Make sure to follow this, because it’s the most important for cementing your understanding:

When we declare an object as an Animal type, the compiler knows to expect dynamic dispatch, since the type of the animal could be mutated or set elsewhere.

cry(), which is a protocol requirement, gets dispatched via a witness table to the cat’s implementation.

Protocol requirement methods will dispatch via a sil_witness_table because the implementation isn’t necessarily definitive at compile-time*.Calling sayHello() on the animal is statically dispatched to the protocol extension’s implementation, because non-requirement methods don’t use a witness table, and the type is known to be an Animal.

We can instantiate a Cat object, which conforms to the Animal protocol but has a definitive concrete type.

This gives the compiler a ton of information which will allow it to optimise things : if the class was final, or whole-module optimisation was turned on, then the methods on Cat will be statically dispatched.

Otherwise, they will be dynamically dispatched via the Animal witness table.When calling the cry() method on cat, the Swift Runtime doesn’t consult the protocol witness table at all, since the concrete type is known.

Therefore, it meows (either statically or dynamically, depending on how your project is set up).Calling sayHello() is similarly executed by the runtime on the concrete cat type, either directly or through table dispatch.

*In this instance, the compiler can know the concrete type of Animal, however Swift does not necessarily optimise this away: optimisation from dynamic to static is great, but not when it actually changes the implementation of a method.

How to intuit dispatch

At this point in the deep-dive, most contributors to Swift method dispatch discourse like to present a table with the types of entity (protocol, class, final class, extension, etc) and the type of dispatch it uses (conveniently ignoring the existence of whole-module optimisation).

In my opinion, though, it’s fundamentally unhelpful to attempt to memorise the various “gotchas”.. It’s exhausting, and more importantly, the compiler optimises away most of what you’re trying to memorise.

The trick? Just consider whether the memory location of the function is knowable at compile-time. If it’s possible, the compiler will do it.

struct methods?

Obviously static.Methods on a class?

These can be made static, but only if the compiler can know the type at runtime.open class methods?

This probably has to use table dispatch to find classes in other modules.protocol requirement methods?

This always needs to use a witness table, even if the type is knowable, so that execution is consistent.protocol extension methods that aren’t protocol requirements?

These just live with the protocol in memory, so can be directly dispatched.

Again, I’m trying *not* to give an exhaustive list, because now you have the power to work out most of these instances using dispatch theory.

Last Orders

Look, I really wanted to show you a cool sample project that showed all these dispatch performances in detail: setting up some structs, classes, and dynamic functions, then running some simple addition functions 1 million times each.

But the compiler kept inlining and precomputing everything!

After some time spent fighting these optimisations, attempting to get to grips with @inline(never), and fighting my instincts to clean up the code, I admitted defeat.

Remember my plight the next time you run into a gotcha, some unexpected behaviour, with Swift, and just remember the compiler is trying its darnedest.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, and you’re hungry for more, consider another deep dive into the compiler:

How to Learn the Swift Source Code

Today I’m selling shovels. A treasure map. The equipment you need to tunnel through the Swift source code and mine out the nuggets of arcane knowledge reserved for C++ and compiler geeks.

Just remember, folks: tip your compiler this Christmas.

This is a full re-write of one of my early, critically under-appreciated posts, back from when I had sub-1,000 subscribers. I’m hoping to upgrade some of my old classics from the vault to spread the joy to my new generation of fans.

The Swift Method Dispatch Deep Dive

Subscribe to Jacob’s Tech Tavern for free to get ludicrously in-depth articles on iOS, Swift, tech, & indie projects in your inbox every two weeks.

Wow, that’s an amazing write! Thanks a bunch !

Gone flex these learnings in my pr reviews's XD :)

Why isn't C++ mentioned? It uses inline, static and dynamic (virtual table).