When To Kill A Project

Dave Verwer's lessons from 30 years of failures (and some successes!)

Welcome to War Stories, where I partner with famous builders in the iOS space to share real-life stories from the frontlines. It’s part narrative, part interview, all swashbuckling fun.

Today I’m working with Dave Verwer, the author of iOS Dev Weekly and co-founder of the Swift Package Index, plus many other projects you might have heard of.

To catch all my War Stories, be sure to subscribe:

Without further ado, here’s When To Kill A Project:

“You have to really carefully cut the bits that aren’t working, and feed the bits that are working.”

— Dave Verwer

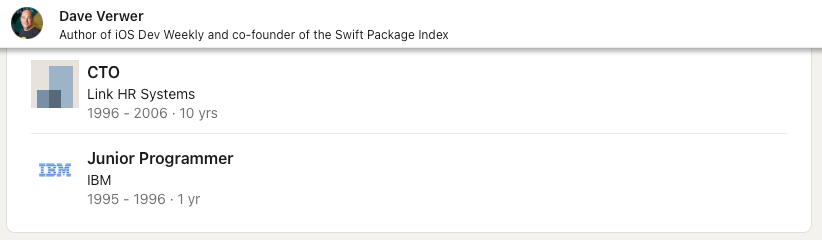

You might know him from iOS Dev Weekly, but Dave’s early career reminds me of another famous LinkedIn profile.

When I asked for tips about how to become a CTO within 10 years, Dave explained it wasn’t quite how it looked. Instead, it was a combination of growing up with the company as it scaled, working way too hard early on, and being the person to take the business online.

Since 2006, Dave has mostly run his own software businesses. When running your own company, you can just do things, so day-to-day work (as well as work-life balance), varies massively based on current projects and commitments.

Dave very modestly refers to himself as “not that good at coding” (which was deeply validating to my impostor syndrome), and explained his strengths lie in being a generalist, who enjoys getting stuck into all the aspects of running a small business: design, coding, research, writing, even doing the accounts.

One more very critical skill is knowing when to kill a project.

We discussed several of these projects, both successes and failures, and hammered out what we can learn from each of them.

iOS Dev Survey

Focus on what’s working, kill whatever isn’t.

— Dave Verwer

Dave wanted to do this for ages. Fortunately, since you can just do things, he did.

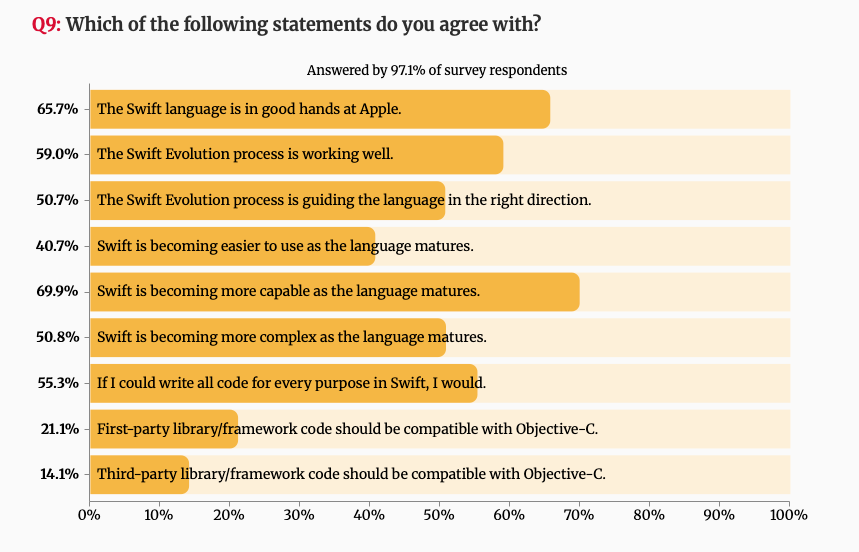

In 2020, he orchestrated the largest ever public Apple platform developer survey.

Dave’s decade spent cultivating a newsletter audience made him one of the only people in the world who could pull this off, and he managed it in a big way: 2,290 developers spent ~30 minutes each filling out a comprehensive survey with the promise that all the data people contributed will be made public in aggregate form.

Dave grinded for months to prepare the questionnaire, set up the website, land some sponsors, market the survey, process the data, and write commentary. It was virtually certain to be a hit.

And.

Crickets.

Despite the enthusiasm from respondents, excitement from sponsors, fascinating analysis, and huge time investment, hardly anyone actually read the survey results.

As soon as it was clear it wasn’t going to be successful, Dave proactively refunded the sponsors (many of whom he still partners with). Reputation is everything when your business is trust.

While the 2019 survey was a flop, a few community members asked whether they could keep it going, and tried again next year. Dave agreed to hand it over, support where needed, and help with publicity, but that added up to a lot of work. When the second survey (still completed by 1,229 devs!) still failed to garner interest, Dave killed it, as it still ate up a lot of his time.

The key lesson here is that you can never predict when something will or won’t work. But you win in the long-term by knowing when to quit, and doing right by everyone.

Tackle Fishing

Market research is essential.

— Dave Verwer

Dave’s company was on a roll after a big success with the Balloons app, and was looking for their next hit.

One of his co-founders was friends with a minor local celebrity in the fishing world. While at the pub, they had the idea to put his fishing knowledge into an app: Tackle Fishing. The team went all-in on production value, even getting a full-time illustrator on staff to make beautiful artwork with parallax-effect animation.

The business model was simple: you pay to download the app 🥹 (ah, better times).

But in their excitement to ship, the team forgot an important step: Market research.

If they spoke to users and focus-grouped some fisherfolk, they’d have noticed a big problem with the concept:

You go fishing to relax, become one with nature, and clear your mind. The last thing an angler wants to do is look at their phone.

The pretty clear lesson here is to talk to your users. Oh, and don’t make apps for your mates based on a conversation at a pub. But we can go deeper than that: when doing market research, never ask someone if they’d pay for something*.

Paying hypothetical money is free, so people will happily fluff up your imaginary future revenues. People pay to have their needs met. Ask about everything around the money, and identify the needs.

*I made this exact mistake with my first startup, where our market research indicated that people would totally pay $10-100 a month to offset their carbon footprint. They did not.

AppReviewTimes

Even successful projects have an expiration date.

— Dave Verwer

If, like me, you began releasing apps around 2016, it might not be obvious why AppReviewTimes was a hit.

In the early App Store, review times were bad. Really bad. Like a-whole-month-of-waiting bad. A-month,-then-you-get-rejected,-then-you-have-to-resubmit-and-wait-several-more-weeks-for-another-review bad. It was bad, basically.

Identifying this common pain, Dave hacked together a simple Rails program to scrape the Twitter (RIP) API (also RIP) for #iosreviewtime and #macreviewtime hashtags, crowdsourcing data in real-time and parsing out averages. This job ran hourly and updated a static web page (the best kind of website).

Dave heard from a few people who would know that the numbers matched the reality of the queue size pretty well. The sample size of ~100 Tweets/day gave enough data to make the site accurate, and provided a solid alternative to refreshing the App Review status page every hour*.

*If someone can do the same thing for the Substack Tech leaderboard please tell me

Nothing went wrong here. The project was a smash hit, with tens of thousands of iOS and macOS devs checking it to feel better about their career choices every day.

The project started to become obsolete when Phil Schiller took over the App Store. In his first 6 months, average review times nosedived to a few days. Job done. Time to shut it down.

People encouraged Dave to keep the site up, lest Apple get lax with times again and they backslide. But with faster review times, fewer people checked the site, and less people Tweeted review times. Without a sufficient sample size, data grew less accurate, meaning there was no longer any reason or ability to keep the site active.

There was no business model with the site. Dave briefly played with ads, but those only work if time-on-site averages more than a couple of seconds. The most money the site ever made was eventually selling the domain: a gaming company bought it as an SEO play, to create high-quality backlinks for themselves. Dave struggled a bit with the decision of whether to sell it for that purpose, but it had been a couple of years since the site had stopped functioning and traffic had almost completely ceased.

With some projects, you want to shut them down. AppReviewTimes is a perfect example. See also, libraries where Apple upgrades its API to include the functionality. Apple is taking over maintenance! That’s a huge win.

Dave deftly sidestepped credit for improving review times, pointing squarely at Phil Schiller for the improvements. The most I got out of him was that maybe AppReviewTimes helped put it on Phil’s radar.

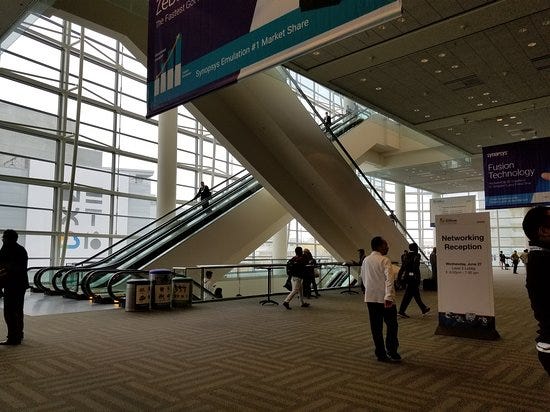

Swift Package Index

This project is still going strong, so doesn’t quite fit the “how to kill a project” theme, but I kept it anyway because I found it interesting.

Swift Package Index was a prime example of skating to where the puck was headed. While at WWDC, by the giant escalators at Moscone: he had a thought that it seemed likely Apple would extend SPM support to iOS the year after.

This opened an opportunity.

Dave built a prototype with a few key principles in mind: Separate the index from the delivery mechanism (unlike Cocoapods). No crawling; ensure intentionality by requesting devs make a PR into a large list of packages. Read the JSON, download manifests, process the packages, and throw them into a database.

Sven emailed Dave with a suggestion for the site: integrate his Arena project so that devs could instantly test packages in a playground. They chatted on a call and agreed that to be a success with the community, the site also needed to be open-source and written in Swift rather than Rails.

Work on the Swift Package Index began a few days later.

They launched just before the next year’s WWDC announcement of SPM support for iOS, positioning themselves to become the default choice for package discovery.

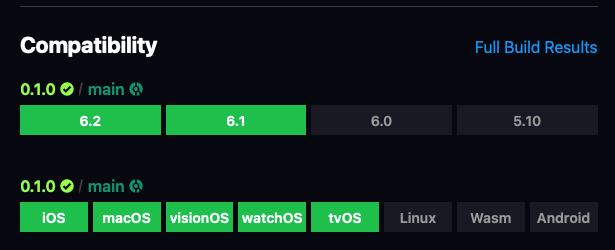

I’m eternally fascinated by iOS devs building into cloud-hosted devtools, so spent extra time picking Dave’s brain about the infra. I asked about the 25% number from the Swift for Android announcement. Basically, it was fairly straightforward to add WASM and Android to their compatibility matrix, which builds each package against each version of the Swift toolchain, on each platform, each time a package update is pushed.

So 25% was the proportion of Swift packages that successfully compiled when run using the Swift for Android toolchain.

The infra is neat: a combination of a big MacStadium cluster of eight M3 Ultra Macs running Apple platform builds 24/7, and an Azure cluster for Linux, WASM, and Android. Very generous contributions from Apple, MacStadium, Microsoft, and the community pay to host all this. Running a popular open source project means people will often happily help cover your costs.

Thanks again to Dave Verwer for taking the time to share his War Stories with me!

If you aren’t already on them, subscribe to iOS Dev Weekly and start using the Swift Package Index today!

If you have a story you’d like to share, get in touch!

If you aren’t a subscriber to Jacob’s Tech Tavern, get every War Story (and much more) by subscribing here:

Dave’s newsletter is my favorite iOS newsletter. I appreciate that it’s curated and formatted nicely. It’s nice to finally read his own war stories!!

That was really good. It’s interesting how much knowledge is hidden away in people’s heads. Thanks for getting this out to the world.